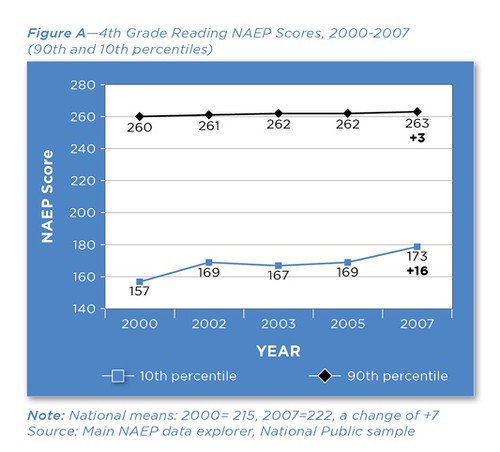

The report doesn't establish causality (and doesn't claim to), but the authors clearly think that NCLB and the standards movement in general is working: working in the sense that the bottom 10% on NAEP are steadily improving their achievement:

This is the first time I've seen the idea that NCLB is working supported by data.

It's also the first time I've heard that it's the bottom scorers, not the "bubble children" who are benefiting from NCLB.

A couple of things for now.

The report doesn't seem to mention the 1995 recentering of SAT scores or the fact that the decline in SAT scores was concentrated at the top. The report practically invites readers to shrug off the "needs" of the top 10% -- if they're already on top, how can they go higher?

Beyond this, I'm somewhat disturbed by the universal acceptance of the idea that "excellence" and "equity" are two separate things. Apparently the policy world is prepared to recognize only two conceivable positions:

- you can have equity or you can have excellence, but you can't have "both"

- you can have equity and you can have excellence; you can have "both"

The possibility that equity and excellence are flip sides of a coin isn't on the menu.

What I've seen, time and again, that if a school isn't doing a good job teaching the bottom 10%, it isn't doing a good job teaching the top 10%, either. It may look like it's doing a good job. But once you factor out the parent reteaching & the tutors, you see that ineffective teaching is ineffective teaching. Period.

I had started to wonder about this in terms of athletic programs. Often people think of athletics and academics as either/or -- and when you're talking about athletics and academics at the highest level of individual achievement, of course they are either/or.

But when you're looking at a school, what goes with what?

Good academics with poor athletics?

Good athletics with poor academics?

I'm coming to the conclusion that's not the case.

No time to give my various "data points" at the moment, so I'll content myself with just one.

Two weeks ago I attended the Sports Orientation Night at C's new school. The place was mobbed. The principal spoke first. Toward the end of this talk he said that 10 or 12 years ago, the school had decided to raise its admission standards. The one thing he regretted at the time, he told his wife, was that the school had always been known for its strong athletic programs. Once they started admitting more academically oriented kids with higher scores, their win-loss records would suffer.

But that's not what happened. Instead, the wins show up; in one year alone the school won 3 more citywide championships than they had in the preceding 7 years. The principal and the athletic director both said they still don't understand why that happened.

To me, it made sense. I'd been noticing that great high schools, academically speaking, tend to have great teams.

A school that's on the march is on the march. They're not on the march here, but phoning it in there. When you're on a mission, you're on a mission.

I understand that trade-offs exist, opportunity costs are real, etc. But I don't think "trade-offs" and "opportunity costs" capture the way a high-performing organization functions.

In fact, I'm sure of it.

Back later.

Actually, I think that the good-academics and good-schools idea you have is all about trade offs and opportunity costs. And high performing organizations understand that, and recognize that the opportunity cost of losing talent is that Someone Else has that talent, and will beat you with it.

ReplyDeleteSelective schools need to find ways to attract the talented students. The trade off isn't between a good basketball player and a good student. The trade off is between spending the time/energy/money to recruit, coach, and challenge talent vs. spending that time/energy/money on something else. High performing orgs know that talent is an asset, and basically every thing else is a liability. You can't have high morale without talent.

But talent in high schoolers comes in the form not of pure, raw unmitigated strength or coordination, but in the form of Someone Who Can Be Coached. Someone who has the discipline to do what's expected, Someone who responds well to demanding expectations. Because unless you're Michael Oher, the single talent on a team sport still isn't enough to propel that team to the top. The whole team has to play together, and it's as weak as its weakest link. This is true in history class and on the baseball field. When you set out to recruit students who won't be disruptive to your mission, who will be leaders and optimistic about your mission, then it doesn't matter whether they are football players, dramatists or math whizzes--they are supporting the goal.

I think high performing organizations just admit their trade offs up front--they can't attract the best students without spending money on infrastructure; if you ignore discipline problems, it's easier in the short term but worse in the long term; if you want excessive teacher autonomy, you won't have all classes following the same curriculum. So they decide on which trade offs they can afford. It works because they've Got A Mission, and the Mission guides their choices.