I'm not sure how journalism works these days.

Last Friday, shortly after

the BLS released payroll data showing 163,000 jobs created in July, the Times posted its story. The American economy, it said, had "continued" its "long slog upward from the depths of the recession." That was the lede.

The next paragraph reported that the economy was "just barely treading water."

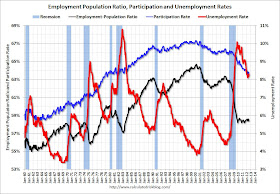

I found this exasperating. Where jobs are concerned, the economy has not "continued" a long slog "upward."

Employment crashed in 2008 and never came back, and there's an end to it. The economy is

slogging sideways.

But even more annoying in some ways, to me at least, the metaphors are mixed.

Barely treading water is not compatible with

continuing a long slog upward. One is up, the other is down

, or down as much as up. A person who is

just barely treading water is not gaining altitude, and I'm pretty sure I remember a time when anyone working for the

New York Times would have known this without having to think about it.

A half hour or so later, the story changed. Someone had cleaned up the mixed metaphor, which was good, but the story itself had gotten worse.

The lede was the same--the economy was still slogging upward (not true for jobs!)--but now the 2nd paragraph opened with the observation that while the payroll survey was better than economists had expected, "no one is yet popping champagne corks."

Yet?

I saw one estimate showing that if the economy continued to produce 163,000 new jobs every month from now on it would take 8 years -- 'til 2020 -- to return to the employment level we had in 2007. Eight years to produce a jobs recovery for a

4-year 5-year slump (to date): nobody uses 'yet' in a context like this.

And nobody

pops champagne corks at the end of an 8-year

slog.

So Take 2 was even more exasperating, and then finally a third version of the story cropped up:

America added more jobs than expected last month, offering a pleasant surprise after many months of disappointing economic news. Even so, hiring was not strong enough to shrink the army of the unemployed in the slightest.

Hiring Picks Up in July, but Data Gives No Clear Signal

By CATHERINE RAMPELL | Published: August 3, 2012

This is the same story! We've gone from the economy slogging upward to economists not popping champagne corks to an army of the unemployed not having been shrunk

in the slightest, and all of this in just a couple of hours.

How does this happen?

How do mixed metaphors and bad metaphors get through copy editors at the

Times, and how does a story completely change meaning within just a few hours?

I'm wondering whether, these days, news organizations post stories as soon as they possibly can, knowing they can clean things up later.

Do newspapers deliberately post first drafts these days?

update 8/8/2012: Anonymous leaves word that

the story changed 9 times.

(click on the images to enlarge)