As the number of year 12 students enrolled in advanced and intermediate maths continues to slide, the chairman of the national committee for mathematical sciences, Hyam Rubinstein, said because maths was viewed as a difficult subject in schools, only the best and brightest were encouraged topursue it at an advanced level.Cross posted here.

"If a school wants to maximise their performance, they may feel that 'if we encourage weaker students not to take maths, our results will look better'," he said.

Pages

Saturday, August 11, 2007

Discouraging news

Friday, August 10, 2007

Upon reflection

Conclusion: I stink at teaching percent.

That about covers it.

But!

I have a plan.

More anon.

...........................

Haven't read email in days - (Premack says NO! So if there are folks who've sent something I haven't answered, that's why - hoping to get back to Entourage tomorrow.)

the pause that refreshes

upon reflection

Plan B

Andrew on Google

If he comes up with any answers, I hope he'll share them with us.

Thursday, August 9, 2007

way worse than you think

Now, for instance:

One place where this movement thrives is El Puente Academy for Peace and Justice in Brooklyn, the city’s first “social justice” high school. The school’s lead math teacher, Jonathan Osler, is using El Puente as a base for a three-day conference in April on “Math Education and Social Justice.”

[snip]

Among those scheduled to speak at the conference is Eric Gutstein, a mathematics education professor at the University of Illinois and a former Chicago public school math teacher. Gutstein’s book, Reading and Writing the World with Mathematics: Toward a Pedagogy for Social Justice, combines Marxist teaching methods [Marxist teaching methods?] with examples of math lessons for seventh-graders. One of these lessons is “The Cost of the B-2 Bomber—Where Do Our Tax Dollars Go?” Its purpose, Gutstein writes, “was to use U.S. Department of Defense data and find the cost for one B-2 bomber, then compare it to a four-year, full scholarship to the University of Wisconsin–Madison, a prestigious out-of-state university. The students had to answer whether the whole graduating class of the neighborhood high school (about 250 students) could receive the full, four-year scholarships for the whole graduating class for (assuming constant size and costs) the next 79 years!” [guess and check!]

Gutstein also recounts how, on the first anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, he was able to convince his seventh-grade math class that the U.S. was wrong to go to war against the Taliban in Afghanistan....

Another of the math conference’s “experts“ is Cathy Wilkerson, an adjunct professor at the Bank Street College of Education. Wilkerson’s only other credential of note (as listed by the conference’s organizers) is that she was a “member of the Weather Underground of the 60s.”

[snip]

After serving a brief prison term, she became a high school math teacher....

Radical Equations

by Sol Stern

So I guess they're not kidding about the shortage of qualified math teachers.

why kids should study the liberal arts: a real-world example

The liberal arts, by the way, are the core "liberal" subjects:

- math

- science

- history

- literature

- philosophy

(I'm embarrassed to say that I don't know how art history or studio art fits in ... sigh.)

Math and science are core liberal arts disciplines, and Finn and Ravitch are quite wrong to imply that the phrase "liberal arts" means literally the arts. It does not. This is why liberal arts colleges invariably have names like "College of Arts and Sciences" or, alternatively, "College of Letters and Sciences."

The term for the subjects Finn and Ravitch are defending is the humanities.

The word "discipline" is important, too. A liberal arts discipline has particular modes of research and reasoning that take years to master and are different from the modes of research in other liberal arts disciplines.

Ed discovered this when he team-taught a course with a literature professor from the French Department. Until that experience, he had no idea how different his mode of reading a text was from a literary specialist's mode.

As Ed put it, "To Richard, a text isn't a document."

Who knew?

The liberal arts disciplines are under chronic attack by progressive educators, who have always and everywhere pressed for "interdisciplinary" course content, as far as I can tell. They won an early victory in the case of history; that's why U.S. kids learn social studies. The best statement I've read on the subject was left in a comment by David Foster on joannejacobs (I think it was joannejacobs), who said (paraphrasing), that "Public schools are filled with people who want to turn all subjects into social studies or crafts."

True.

It's hard to defend the liberal arts. At least, it's hard for me. I don't know enough about them even to know what I'm defending half the time.

After reading Hirsch on the importance of background knowledge, and after discovering that the possession of background knowledge causes you to acquire new knowledge faster, it occurred to me that there is a striking pragmatic case to be made for giving children a broad education in the liberal arts, which is that the liberal arts would actually turn them into the flexible & speedy little learners the 21st century is apparently going to require.

This morning I encountered a terrific example of this.

The Times had a story on the new NAEP test of economics knowledge, which included these two sample questions.

I didn't know the answer to number 2. I'd never heard of price equilibrium (is that the term?); I'd never seen a chart like this; I knew nothing about the subject.

However, because I have a relatively decent knowledge of the relevant liberal arts, the instant Ed explained it to me I got it. The instant. I had a moment of extremely rapid learning because I have an education in the core liberal arts disciplines.*

The relevant liberal arts are, in this case:

- math, meaning algebra 1, which includes the topic of linear functions

- probably science, which frequently uses concepts like equilibrium and homeostasis

- probably history and political philosophy, both of which allow you to understand that people can and do act as societies, that black markets have always sprung up in societies that attempted to set prices, that only a dictatorship can effectively enforce laws against black markets, etc.

The liberal arts disciplines are "the basics" one needs to become a lifelong learner.

update

Remind me not to rag on Diane Ravitch anymore.

the NCTM on interdisciplinary learning in math: An interdisciplinary approach to science, mathematics, and reading: Learning as children learn

American Academy for Liberal Education

The Seven Liberal Arts (Catholic Encyclopedia)

Phi Beta Kappa Society statement of support for AALE

Philosophy of Liberal Education

Coaches Shouldn't Teach History by Diane Ravitch

* I had a terrible time with the one economics course I took in college. I absolutely could not get the idea of a group of consumers in the aggregate. I kept thinking, "What if some lady decides not to buy panthose?" You may laugh - hah! - but in fact, the idea of macroeconomics, and of statistical aggregates, does not come naturally. If you're going to pick it up quickly, you're going to need a better high school education than I had.

timers - advice from Commenters - THANKS!

from James:

we have a simple digital kitchen timer. you set the time you want 5 10 15 minutes, hit start and it counts down and beeps at 0. then reset and go again.

nothing fancy.

from Matthew K:

Yep, digital kitchen timer, very small, under $10.

from Steve H:

My mother has one of those timers even though she is in her 80's. It's going off all of the time. If it were mine, I would stomp on it.

[yup. that's my problem with the kitchen timer concept. have I mentioned I've been making heavy-duty use of our new StressEraser?]

also from Steve H:

Remember, hard work pays off sometime in the future; procrastination pays off right now. Stop and smell the roses.

and:

I find that a lot of my programming work gets done in fairly short times of intense concentration. The hard part is getting started. The way I try to deal with this is to leave off at "easy spots". I don't like to leave off at the end of a big task. It's too hard to get started on something new. If I leave off at an easy spot, then my brain doesn't have to work hard the next time I pick up the work. Once I get going, I find it easier to deal with more difficult problems.

me again:

This is great advice, which I normally try to follow. Unfortunately this chapter of the book I'm writing with Temple doesn't have any easy spots (true--not ironic).

It doesn't have any easy spots BECAUSE I DON'T HAVE ENOUGH BACKGROUND KNOWLEDGE IN THE SUBJECT I'M TRYING TO WRITE ABOUT.

When you have to look EVERYTHING up on Google (or, now, on NYU's Bobcat system), you're in hell.

I am a living exemplar of the 21st century lifetime-learners scenario the ed schools foresee for all citizens, across the board: I am attempting to produce a large & complicated project based not on knowledge I acquired through study and SAFMEDS, but through my powers of logic and my ability to look things up.

That's doing things the hard way.

from Eric:

The Timex Expedition wristwatch has a timer with a "flip the hourglass" repeat mode. Mine is set to 6 minutes and enabled when I barbecue.

It's also useful if I find myself posting at blogs instead of crafting educational reform.

Oops.

Eric!

Get back to work!

prices said:

These types of timers are also used for yoga practice. They tell you when you should change poses. Now & Zen makes an expensive but pleasant sounding chime. (got one for the wife)

Perfect!!

I wasn't going to think of that one.

question:

Why am I a person who, when trying to figure out what an interval timer is & who sells them, does figure out boxers use them but does not figure out people who do yoga would use them, too?

Somebody should have sent me to military school when I was young.

I can see that now.

...............................

THANKS!

..............................

Speaking of the StressEraser, we've had it for a couple of days now, and it's pretty cool.

Ed bought it because he's been going through a wicked phase of insomnia; that's why the kids' psychiatrist recommended it. For sleep.

I was skeptical it would work for sleep, but darned if it didn't put him to sleep last night. He said he almost dozed off a couple of times before he'd reached to the requisite 100 "points." He had to rouse himself to carry on de-arousing himself.

So we'll see.

For me, the effect is subtle but great. I'm not sure what it does exactly; I assume it's something you do in yoga and/or meditation. (And definitely not not something you do in boxing).

You breathe in and out to a count of four while the StressEraser takes your pulse. If you breathe "correctly" (I don't know how the machine defines correctly) you get one point each breath. During the day you're supposed to go to 30 points; you go up to 100 points at night, before bed.

I'll keep you posted.

help desk - timers

you heard it here first (possibly)

StressEraser on YouTube

a possible case of buyer's remorse

gadget of the week

Tuesday, August 7, 2007

help desk - timers

Here’s another technique that works pretty well to keep me on task: Sometimes I use a timer that beeps every five minutes. And when the timer beeps, I mark on a graph, whether I was on task or off task at the time of the beep. That’s a great one for cutting down on my daydreaming. It gives me a rule that specifies a more immediate deadline. Stay on task, because that timer is going to beep pretty soon, and you don’t want to ruin your graph. So instead of having a daily deadline, or an hourly deadline, I’ve got a sort of five-minute deadline, except I’m never too sure how soon it’s going to be.

I'll Stop Procrastinating When I Get Around to It

by Dick Malott

Chapter 3: How to Get Yourself to Write

So here's my question.

Where does one buy an every-five-minute timer?

Behaviorists toss off this advice like the rest of us just know that:

a) every-five-minute timers exist

and

b) where we go to get one

Well, I don't know.

When I first heard tell of folks setting 5-minute timers to find out whether they were on task, I didn't want to know whether or not I was on task every 5-minutes.

But now I do want to know, but I don't have a timer and I don't know where to get one.

Thank you in advance.

[pause]

The word interval has just popped into my head.

interval as in interval timer

There must be such an animal.

[pause]

Is this it?

They seem to have quite a few of these things for boxers. Apparently boxing is easier than writing. They only have 2 to 3 minute intervals.

Or maybe that means boxing is harder.

Premack Principle redux

I guess employing the Premack principle means I should remap my software program's option file before I post this.Yup.

That's what it means, alright.

percent problem from Math Notations

There are 20% more girls than boys in the senior class. What % of the seniors are girls?

The Comment thread is fantastic, as is the thread on the follow-up post.

And here is Denise, of Let's Play Math, on the subject of percent:

Percents are one of the math monsters, the toughest topics of elementary and junior high school arithmetic.

Now she tells me.

As it happens, I agree. Percent problems are he**. That is my final word on the subject. H-e-double hockey sticks.

I am spending my entire summer trying to teach percent to you-know-who, when I had planned to spend my entire summer practicing up on factoring polynomials and such.

Turns out factoring polynomials is child's play compared to decimals, fractions, and percent.

Back to Denise:

The most important step in solving any percent problem is to figure out what quantity is being treated as the basis, the whole thing that is 100%. The whole is whatever quantity to which the other things in the problem are being compared.

Denise's post, which she calls the search for 100%, puts me in mind of Ron Aharoni's book, Arithmetic for Parents (scroll down). Carolyn and I both loved Aharoni's article for American Educator, What I Learned in Elementary School.

Here's his passage on the fifth operation of arithmetic:

In addition to the four classical operations, there is a fifth one that is even more fundamental and important. That is, forming a unit, taking a part of the world and declaring it to be the “whole.”

I love that!

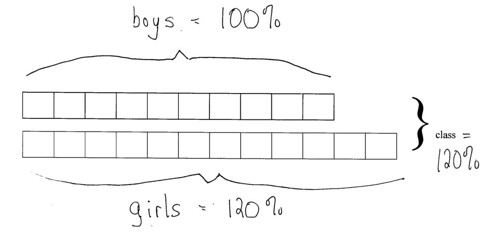

So, on to our problem. The folks at Math Notations discuss the ambiguities of the English language in percent problems. I found the problem's wording ambiguous myself, and used a bar model to clear it up:

large image here

In the bar model the number of girls is definitely 20% greater than the boys. Plain as day. However confused you may have been by the words, there aren't a lot of different ways to draw the girl bar, assuming you've drawn the boy bar correctly (which you won't have done if you're a middle school student, but never mind).

After you've drawn a 10-square bar model to represent the boys and a 12-square bar model to represent the girls, you see that to get the total class size you're going to have to add 100% to 120%.* There is just no way around it.

Without a bar model (and even with a bar model) this is brutally confusing, because in everyday language "whole" and "all" mean "100%."

It's difficult to break set, as my cognitive psychology professors used to say.

Making boys the "100%" requires big-time set-breaking, because when you're given a problem involving boys and girls in a class at school, you think of the boys as the boy-part of the class and the girls as the girl-part, with the class being everyone, i.e. the whole, i.e. 100%.

The idea of adding 100% to 120% to get a class of 220% is just frankly nuts in terms of everyday language and experience. A class can't be 220%. We know this.

..........................

I wonder if this problem would be more solveable if you wrote it in nonsense words?

There are 20% more meps than jeps in the pile. What % of the pile are meps?

None of those words, including "pile," screams out at you: I am always and forever 100%; trifle with me at your peril.

.................................

I walked Christopher through this problem.

Just because I could.

.................................

update from Susan J:

To me the most natural way of doing the original problem is two equations in two unknowns:

Either

g = 1.2 b

g+b = 1

and then convert the answer to per cent or

100 g = 120 b

g+b = 100

The one encouraging aspect of the two posts at Math Notations was that apparently kids who know algebra pretty well can solve this problem. I assume they use Susan's two equations, but I don't know.

Actually, that was very encouraging.

On a related subject, I'm moving into the Saxon/Dolciani "percent charts," in an effort to bring home the idea that if you have 20% more girls than boys you will have 1.2b -- only I'm starting with a whole of 100% (I wonder if that's a bad idea...)

The charts look like this:

original price 100% $50

discount 10% $5

new price 90% $45

A word problem would be something like this:

Catherine bought a new blouse for $45. It had been reduced by 10%. What was the original price?

original price 100% p

discount 10% $45

new price

The charts help you see that if you're taking 10% off the price, then you're paying 90% of the price (something I didn't realize until two years ago, when I did a percent problem in Saxon).

I'm having a terrible time getting C. to see that we're dealing with proportions here, and that percent problems can always be solved as proportions -- and that the chart is a cool way to show you all the various proportions you can employ to deal with simple problems like these.

Probably time to back up to something simpler.

Tomorrow I'm going to have him do a page of equivalent fractions using percent fractions and non-percent fractions.

e.g.:

75% off $60 means:

25/100 = x/60

I'll try to combine these with the charts and see how that goes. Must re-read Dolciani & Saxon, too.

..................................

Fantastic posts and threads:

The search for 100%

wrong answer: girls are 60% of the class

there are 20% more girls than boys

percent word problems revisited

and, at ktm-1 (you may have to hit refresh a couple of times):

Aharoni article, part 1

Aharonic article, part 2

Ron Aharoni on the 5th operation of arithmetic

Ron Aharoni on teaching fractions

order Arithmetic for Parents

Ron Aharoni's home page

* or 10 to 12, as the case may be

Monday, August 6, 2007

Help for the afflicted

Karen A left this comment today:

Yikes! Somebody needs to stop me! (I'm in major procrastination mode--I'm supposed to be writing a paper.)This is your lucky day, Karen A!

It just so happens that I, too, have been in major procrastination mode for lo these many moons, and I have found the answer:

the Premack Principle

The Premack Principle sounds like something you already know, but it isn't.

Sure, sure, we all know positive reinforcment is a good thing.

We all know we should put first things first.

What we don't know -- what I didn't know, at any rate -- is this whole business about reinforcement hierarchies. To wit: there are tons of things you don't want to do, and a bunch of things you do want to do, and these things can be ranked.

Then, once you've ranked them, you can pick something you don't want to do -- any old thing you don't want to do, not just the one big thing you don't want to do (in my case: stay up all night and write my book) -- do that one thing; then pick something you do want to do and do that.

And here's the miracle: after you've done this for a day or two, you start to want to do the things you don't want to do.

Not only that, but the Premack Principle works with your middle school child, the one who thinks the problem with parents is they constantly threaten to take away rights from their children.

Seriously.

Take it from Jon Bailey and Mary Burch:

Basically the Premack Principle involves setting up the rules in the house so that the preferred behavior (watching TV) is used as a reinforcer for the nonpreferred behavior (helping with chores).Translation: no "break" after school.

p. 3

The "break" after school has been sacrosanct around here. C. needs a break after school. That's the concept. He's been at school all day; school is hard; he needs a break.

This summer the after-school break made a seamless transition into the after-camp break. C's been hard at work playing tennis all day; he needs a break when he gets home.

Which means C. comes home, plops down on the sofa, and begins playing video games with Christian, leaving me to nag, order, demand, and, yes, threaten to take away rights.

And that's just the beginning. When I finally get him to the table, we have negotiating.

If I do Megawords I'm not doing Vocabulary Workshop.

If I do decimals I'm not doing word problems.

Etc.

That's all over now.

Last Tuesday or Wednesday, I squelched the after-camp breaks. By the weekend things were running so smoothly that on Saturday morning C. came into my office at 10:30 a.m., sat down, sighed, and said, "What do I have to do?"

Then he pitched a fit, but still. By noon he had done everything I wanted him to do.

He was amazed. He kept saying to Ed, "I'm done with my work."

And Ed kept replying, "Doesn't it feel good to get it over with?" (great attitude, that!)

Sunday morning I got up and started awarding myself mental points for doing things I didn't want to do. I was banking my points, saving them to spend on doing things I did want to do. This turned things I didn't want to do into things I did want to do (points!) which got a little confusing because if I wanted to do something I didn't want to do because I would get points if I did it, didn't that make it something I did want to do after all and thus something I shouldn't be getting points for doing?

This put me in mind of the possible urban legend about the one-question essay exam some Harvard psych professor was said to have given his class, namely: what is a stimulus?

I decided not to worry about it. I was tearing around the house looking for things I didn't want to do that I could go ahead and do right then and there before we had to get to church. Points!

En route to church I explained the Premack Principle & the point system to C, who took it to heart at once.

Then, in church, we wrangled over how many church points (church being down there with word problems in C's reinforcement hierarchy) he was now losing for rudeness and failure to attend to the sermon.

When we got back home he had one don't-want-to-do facing him, which was to read a page of the Bible. This task is the result of a negotiation we'd had a couple of weeks before, when C. had said he shouldn't have to work on Sundays, and Ed backed him.* So I said, Fine, you don't have to work on Sunday if you read the Bible, and Ed didn't have the nerve to intervene on that one.

C. also needed to mow the lawn, but since he gets paid to do that, and since it was his idea to start mowing the lawn, lawn-mowing was somewhere in the middle of his hierarchy.

He read one page of the Bible practically the instant we got home.

Then he mowed the lawn.

Then he lay down on the sofa, snapped on his video game, fixed me with the wolfy smile of the victorious, and said, "I have all my play points for the rest of the day."

..................................

I will be back tomorrow with Dick Malott & his online book on procrastination.

Chapter 3: "How to Get Yourself to Write."

* Have I mentioned Ed is Jewish and agnostic? People will do anything not to hear middle schoolers fighting with their moms about word problems.

cats and dogs living together

ISBN 1-881317-15-3

On its In-Depth page, the Morningside Academy, in Seattle, whose students "typically score in the first and second quartiles on standardized achievement tests in reading, language and mathematics," makes parents this offer:

Morningside Academy offers a money-back guarantee for progressing 2 years in 1 in the skill of greatest deficit. In twenty-five years, Morningside Academy has returned less than one percent of school-year tuition.

from Chapter 6: Comprehension, Critical Thinking, and Self-Regulation

Morningside has wrestled with the problem of guaranteeing that skills taught in isolation truly become an integral part of the everyday activity of the learner. Two methods that we are evolving are designed to bridge typical behavioral skill instruction and useful, real-world application in the spirit of progressive education and John Dewey. When we discuss our procedures with developmental psychologists, constructivist educators, and others outside of the field of applied behavior analysis, we have found them receptive. This is in part a response to our respect for many of their philosophies, methods, and materials. Many of these colleagues maintain activite dialogue with us in our joint effort to find and develop technologies of teaching from basic skills to inquiry and project-based learning.

constructivist behaviorists!

something new under the sun

Here's what they have to say about critical thinking:

Morningside directly instructs and monitors improvement in strategic thinking, reasoning, and self-monitoring skills. Strategic thinking is the glue that allows students to employ component skills and strategies in productive problem solving.... Morningside's instructional and practice strategies build tool and component skills that are needed to solve problems. In addition, most of our students need direct and explicit instruction in "process" or "integrative" repertoires--methods that help them recruit relevant knowledge and skills to solve a particular problem. At Morningside we have found that these strategic thinking skills, characteristic of everyday intellectual activity, are not automatic by-products of learning tool and component skills.

Does this contradict the notion that teaching to fluency, as opposed to mastery, produces contingency adduction? (And see here.)

Are the authors saying that Morningside students have more problems generalizing knowledge to new contexts than students who are doing well in the public schools?

Or are they saying that fluency doesn't increase generalization after all?

I'm getting the feeling that no one really knows how, exactly, critical thinking, problem-solving, and knowledge transfer emerge. As best I can tell, the most that is known is that they don't emerge before mastery of component skills and concepts within a particular domain of knowledge.

More from the book:

There are a number of reasons why traditional efforts to promote creative thinking and problem solving have not been wholly effective. First, watching someone else solve a problem does not reliably teach the process. Second, in routine practice, problem solving behavior is private behavior that other learners can't observe. Third, cooperative problem solving often reinforces already-existing problem solving repertoires of some students in the group, but doesn't enhance the skills in others, even though everyone may come away from the group believing they have "solved the problem."

[snip]

At Morningside, we view the failure to self-monitor and reason during problem solving as a failure of instruction rather than as a failure of the learner. This perspective has provided a challenge to develop instructional strategies that turn learners into productive thinkers and problem solvers.

A note: for those of you who aren't familiar with behaviorism, this is a -- or even the -- core tenet of the field. If an instructional approach isn't working, the problem lies in the instruction, not the student. Or, rather, the problem lies in the contingencies; that might be the proper way to put it (don't know). I'm not sure you could be a behaviorist without subscribing to this principle.

This principle -- it's the teaching, not the student -- led Irene Pepperberg to her breakthrough with Alex the parrot (chapter excerpt), by the way.

Back to Morningside:

Thinking Aloud Problem Solving

To develop these strategies and to provide students with a set of self-monitoring, reasoning, and problem solving strategies, Morningside turned to an approach developed by Arthur Whimbey and Jack Lockhead in the 1970s...They developed Thining Aloud Problem Solving (TAPS) to improve analytical reasoning skills of college students. Perhaps the most impressive evidence of its effectiveness comes from its use at Xavier University in a four-week pre-college summer program for entering students. The program, Stress On Analytical Reasoning (SOAR), was replicated over several summers at this perdominantly African-American college and produced stunning results.... Participants gained 2.5 grade levels on the Nelson-Denny Reading Test and an average of 120 points on the Scholastic Achievement Test. (p. 122)

This assertion flatly contradicts the conclusion of cognitive science that critical thinking and problem solving cannot be taught directly, at least not separately from extensive teaching of content. At least, I think it does; I don't know what kind of domain knowledge was involved in this program.

Interesting.

the cog-sci position

The Mind's Journey from Novice to Expert by John T. Bruer

A few of these programs, such as the Productive Thinking Program (Covington 1985) and Instrumental Enrichment (Feuerstein et al. 1985), have undergone extensive evaluation. The evaluations consistently report that students improve on problems like those contained in the course materials but show only limited improvement on novel problems or problems unlike those in the materials (Mansfield et al. 1978; Savell et al. 1986). The programs provide extensive practice on the specific kinds of problems that their designers want children to master. Children do improve on those problems, but this is different from developing general cognitive skills. After reviewing the effectiveness of several thinking-skills programs, one group of psychologists concluded that "there is no strong evidence that students in any of these thinking-skills programs improved in tasks that were dissimilar to those already explicitly practiced" (Bransford et al. 1985, p. 202). Students in the programs don't become more intelligent generally; the general problem-solving and thinking skills they learn do not transfer to novel problems. Rather, the programs help students become experts in the domain of puzzle problems.

Critical Thinking: Why Is It So Hard to Teach? (pdf file)

by Daniel Willingham

After more than 20 years of lamentation, exhortation, and little improvement, maybe it’s time to ask a fundamental question: Can critical thinking actually

be taught? Decades of cognitive research point to a disappointing answer: not really. People who have sought to teach critical thinking have assumed that it is a skill, like riding a bicycle, and that, like other skills, once you learn it, you can apply it in any situation. Research from cognitive science shows that thinking is not that sort of skill. The processes of thinking are intertwined with the content of thought (that is, domain knowledge). Thus, if you remind a student to “look at an issue from

multiple perspectives” often enough, he will learn that he ought to do so, but if he doesn’t know much about an issue, he can’t think about it from multiple perspectives. You can teach students maxims about how they ought to think, but without background knowledge and practice, they probably will not be able to implement the advice they memorize. Just as it makes no sense to try to teach factual content without giving students opportunities to practice using it, it also makes no sense to try to teach critical thinking devoid of factual content.

I would sure like some help on this issue, seeing as how I am living in failure to transfer land. For the time being I'm going to carry on assuming fluency will help -- fluency and lots of practice with word problems:

Give me a problem which you think is not by type, and I shall invent ten similar problems which will put it into a type. In fact, I often have to do this when I teach: first I solve a problem at the board, then I give a similar problem for all to solve in class, then I give a similar problem as a homework, then I give a similar problem on a test. All these stages (often more) are necessary, otherwise many students will not grasp the method.

Between Childhood and Mathematics: Word Problems in Mathematical Education (pdf file)

by Andrei Toom

Between Childhood and Mathematics: Word Problems in Mathematical Education (pdf file)

Word Problems in Russian Mathematical Education (pdf file)

How I Teach Word Problems (pdf file)

The Executive Brain

Meet Alex

Group problem solving

There is much to be learned from the gifted.

Clueless Mom, a licensed math teacher, is always learning new things from her mathematically gifted nine year old, with whom she seems to now be nearly neck and neck in the area of deep problem solving up to Algebra.

After solving an SAT question with her son by means of group effort (that is, the two of them putting their heads together), CM offers some preliminary observations about group problem solving in school.

They are not hard and fast conclusions--only some out-loud thinking.

Read Group Problem Solving on Clueless Mom of Gifted Kid's blog.

Sunday, August 5, 2007

I love this age

Megawords 4

Worksheet 22-M

directions: Look at List 22. Choose five words and write them in sentences below.

I need permission to put the politician in a submission hold for having a collision with the musician.

Worksheet 23-D

Remember these exceptions to the spelling generalization above.

damage manage savage

Make up a sentence that includes all three of them.

The savage couldn't manage the damage he did to the explorer

If that doesn't persuade you to pop for 8 years-worth of Megawords texts, then I don't know what.

Mr. KUMON

Copying sentences can be especially helpful for improving writing skills if done as Ben Franklin did -- from memory.

My 5th grade daughter is in her second month of Kumon reading, and this week’s worksheets include copying sentences from memory. First, she is instructed to read a short paragraph from a story. Then, she is given a few related sentences to write from memory. The instructions are: “Read the sentence until you can remember it. Then write the sentence.”

I had no clue about the value of this exercise, and I don’t recall that she ever had this in school. Now, I’m starting to understand how this can be beneficial. I’ll ask “Mr. Kumon”, (that’s what my daughter calls him) next time about this.

I don't know why I bother.

Obviously KUMON has already figured the whole thing out. Talk about reinventing the wheel.

I thought "text reconstruction" sounded like a good idea the first time I read about it in The First American by H. W. Brands. But until I saw C's results, I had no idea how useful this technique might be.

It certainly didn't cross my mind that text reconstruction would give me so much insight into what C. needs to work on. It's not just an instructional technique; it seems to work as a diagnostic tool, too.

This fall Ed and I are going to ask to see C's state ELA exam. I mentioned the vagaries of the ELA assessment in a Comment on another thread. C.'s score was 10 points below the cut-off for a 4, but he has a 95% "percent correct" average on the test. Apparently you need 97% or 98% correct to get a 4.

This sounds like a distinction without a difference.

Still, because of the number of multiple choice items, I assume C. had to have lost points exclusively on written responses, which makes sense. His writing isn't remotely as good as his reading. So we need to see his test.

I also assume the state isn't going to be able to tell us why he lost the points he did. The school probably won't be able to tell us, either, because they seem to be pretty much tearing their hair out over the whole thing, and rightly so as far as I'm concerned. The year before last -- the first in which the test was administered -- kids they thought had passed turned out to have failed instead, and scores on the front of a student's test report sometimes didn't match up with scores on the back of the report. Twice I was told the department had "calls into" the state and were waiting to hear back.

Maybe I'll put a call into the state.

I've got the number.

Point is: the whole thing is shrouded in mystery, as my friend M. would say, only in this case the mystery is coming from the state, not the school.

I think the text reconstructions will help. We'll have a more "granular" sense of C's writing when we see the scored test; we'll be able to look at his written responses and either spot what the state rubric found problematic or spot what we find problematic.

We'll see.

In any case, it's clear to me that cohesion devices are going to be a focus around here for the foreseeable future.

The Paragraph Book

Susan S has been using The Paragraph Book with her son this summer. I ordered it, too, on the strength of her recommendation, and while I haven't had time to dig into it, it looks terrific.

I especially like this piece of advice the author gives students about the structure of a paragraph:

FIRST

NEXT

THEN

FINALLY

acronym: FNTF

I'm going to teach this acronym to C. I'm not sure it will help with cohesion devices per se, but I do think it gives one a mental guide to paragraph structure.

Besides, the difference between "NEXT" and "THEN" is cool.

update from le radical galoisien re: cohesion devices--

Well I am sure the material must be very competent, it seems slightly ironic when a summary about text comprehension requires several re-readings to be comprehensible.

I wish I'd said that.