De plus en plus d’enfants en seraient atteints. Vraie pathologie ou effet néfaste des methods?

Il y a trente ans, les orthophonistes attendaient le client. Aujourd'hui, ils refusent du monde », constate Colette Ouzilou, orthophoniste d’experience. Auteur d’un ouvrage virulent sur le sujet (1), elle accuse les methodes d’apprentissage globales ou semi-globales, qui demandent a l’enfant de construire seul son savoir et de devenir le sense de mots. « La lecture et l’ecriture sont des codes. Il faut les enseigner. » Dans les années 1960, la plupart de ses patients souffraient de bégaiement, d’aphasie, bref, de réels troubles du langage. À partir des années 1970, elle a vu apparaître, en même temps que les nouvelles méthodes d’enseignement de la lecture, une première vague de lecteurs défaillants. Aujourd’hui, la quasi-totalité des enfants consulte pour des problèmes d’écriture. D’après elle, sure les 10% d’élèves qui arrivent en consultation, 1% a peine souffrirait de réelle pathologie. Les autres ? Des élèves « dysorthographiques » auxquels il manque des bases. Bien sûr, la plupart des pédagogues s’insurgent, rétorquant que le pourcentage de dyslexiques est le même dans la plupart des pays. Selon eux, cette « épidémie » serait due, pour l’essential, a la pauvreté du langage de certains enfants. « Pour les enseignants, c’est une manière de se fausser, pour les parents, de s rassurer, constate un instituteur de CP. «Du coup, tout le monde en redemande. »

Natacha Tatu

(1) « Dyslexie : une vraie-fausse épidémie », Presses de la Renaissance, 212 p., 15,10 euros, 2001.

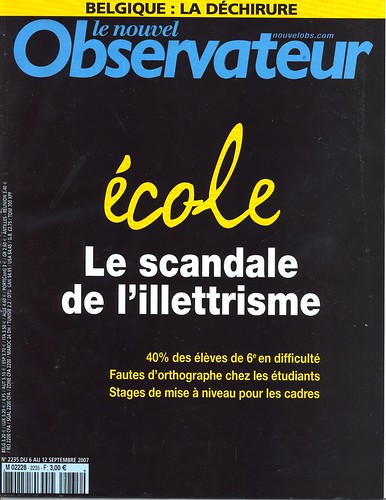

le nouvel Observateurs

N° 2235 du Au 12 Septembre 2007, p. 12

......................................

translation:

Is it really dyslexia?

More and more children are being affected. True pathology or harmful effects of teaching methods?

“Thirty years ago, speech therapists didn’t have enough clients. Today they are are turning people away,” says Colette Ouzilou, an experienced orthophonist. The author of a fiercely critical work on the subject, she condemns the whole language or balanced literacy teaching methods, which require the child to construct knowledge and tease out the meaning of words on his own. “Reading and writing are codes. You have to teach them.” In the 1960s, most of her patients suffered from stuttering, aphasia, in short, real language problems. Beginning in the 1970s, at the same time as new methods of teaching reading came into being, she began to see a first wave of failing readers. Today almost all kids consult her for problems of writing. According to her, of the 10% of all students who have speech therapy, only 1% [of that 10%] have a real pathological condition. As for the others, those diagnosed with reading dysfunction, their real problem is a lack of the basics. Of course, it goes without saying that most teachers disagree with this analysis, replying that almost all countries have the same percentage of dyslexics as we do. According to them this “epidemic” is due in essence to the poor language environment of certain children. “For the teachers, this explanation is a way to absolve themselves of responsibility. For the parents, this is a way of reassuring themselves. Everyone asks for more of the same. [not sure about this last sentence]

Le scandale de l'illetrrisme (nouvel obs: the scandal of illiteracy)

dyslexie, vraiment? ) (nouvel obs: true dyslexia?)

Comment en est-on arrivé là? (nouvel obs: How did we get here?)

French spelling

Why English speaking children can't read

Lucy Calkins on teaching children to write

Becky C on starting at the top

instructional casualties in America

curriculum casualties: figures

forcing hearing children to learn as deaf children must

Rory: I frickin' hate whole language!

thank you, whole language

9 comments:

How strange it is that I would read this post today! Only an hour ago I saw another mom whose son attends the same elementary school, and we were lamenting over our sons lack of reading and writing skills.

She said, "I have a sick feeling in my stomach."

Heh, French writing is a major problem for many even francophone children because of all the homophones.

Curiously however, at the age of six, most French children can spell on average 75% of the words they are given (even if they don't know them) while for English it is 45%. (For relatively phonemic languages like German or Italian, the percentage approaches 90% to 95%.)

Absolutely.

And the French schools have all dropped le dicteé.

Well, as I understand it, the issue with English is the number of root languages, if that's the right term.

Now that I see you're heading towards linguistics (did I get that right?), you might be interested in Louisa Moats' work.

I'll post shortly. She has a nice article on spelling research in American Educator.

Yup! I think I would. I'm interested in linguistics, but I'm not sure what job I want to get with linguistics. But it's my belief that teachers equipped with knowledge of linguistics can make better language teachers, both of native languages and foreign language acquisition.

I might take a double major of linguistics and physics, since really linguistics started out as a hobby and I didn't start thinking about it as a route of education until sometime last year.

"And the French schools have all dropped le dicteé."

Have they? I'm curious about about what happens in the French schools. I know they must be fairly rigourous what with the standardised bac and all.

I play in a Francophone gaming clan, and while they write announcements formally a lot of my clanmates simply write phonetically when chatting to each other. A lot of the "grammar" you see in writing is simply not part of the grammar in speech anymore.

In English you usually have some correlation, like even though you have the "ow" in "cow" and "flow" signifying two different sounds, if you removed the "w' from "cow" you would get a different pronunciation.

Whereas in French, removing the ending -s " in say, "toutes ces personnes" is of virtually no consequence to pronunciation. So I often see "toute ces personne" (all these people), where the plural in "ces" is kept in writing (because there is a vowel difference between ce, cette and ces) but the ending -s of the other words are not.

I don't think chatspeak is the cause of the writing problems (rather the other way round), seeing as problems occurred from the 1970s. I'm curious about dyslexia in other languages.

"Well, as I understand it, the issue with English is the number of root languages, if that's the right term."

Hmm, sort of. The problem is that English writing is actually a combination of many different spelling systems. The fact that English borrows from so many languages would be of no consequence if phonemes were represented consistently. For example, Malay borrows from Sanskrit, Chinese, Persian, Portuguese, Arabic, etc. but as I am aware spelling is not an issue.

Also, the printing press was invented before the Great Vowel Shift that occurred just after Shakespeare's time. If you read Shakespeare, you can notice many rhymes that look like they rhyme in spelling but not in pronunciation.

lrg--

Physics and linguistics?!? Now that's quite a combination. I see you as a university professor some day (and I mean that as a good thing).

I don't think chatspeak is the cause of the writing problems (rather the other way round), seeing as problems occurred from the 1970s.

I agree.

I'm curious about dyslexia in other languages.

Apparently Italians have a significantly lower rate of dyslexia, apparently because the language is more....don't know how to put it.

More regular, I guess.

Tex

yeah, I had the same thought

Post a Comment