Pages

Friday, June 20, 2008

The Reality of Differentiated Instruction

Who can come up with different examples?

Increase In Special Education Enrollment: Funding Driving Rise, Or Real Increase?

Greene and Foster wrote a Pajamas Media (PJM) article that alleges that the increase in special education enrollments is a result of a "bounty" schools get for SpEd students, rather than an increase in need.

Foster and Greene maintain that schools have a financial incentive to label kids as learning disabled. In fact, schools actually have a disincentive to diagnose kids. The money that they receive from the federal government is a fraction of the money that they actually spend on special education. The federal government only pays for 17%

of the expenses for special education. State and local governments must pick up the rest of the tab. In our town, nearly half of the local school budget is devoted to special education.

I agree with Laura's thesis that much of the rise in SpEd enrollment arises from disabilities that weren't recognized in earlier eras.

But, beyond that, yes, many things have changed since the 1980’s. The definitions of LD have been refined in the law, as well as the diagnostic criteria. In the 80's the criteria were primarily discrepancy based (performance below ability), which meant that a low IQ score (if it was too high to qualify for MR/DD criteria) excused low performance. There was also the two standard deviations below the mean criteria–also not current. And, as I pointed out, the incentives may have changed. Where labelling a kid was previously a way to move them out of the accountability system (as well as the classroom, or even the school), there are more protections now that disincentivize that option. In fact–wasn’t there a school in California that was relabelling kids as non-disabled to get below the “n” size for required reporting?

Previously at I Speak of Dreams:

Thursday, June 19, 2008

stagnation at the top

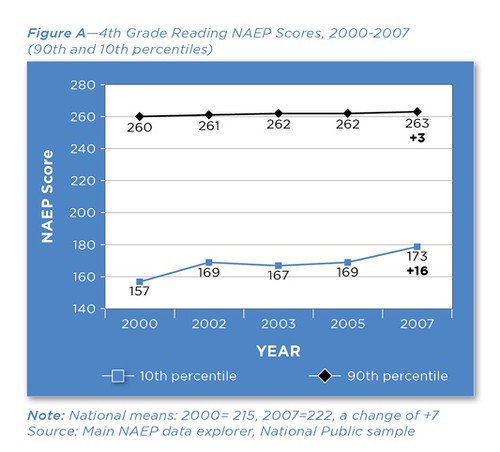

The report doesn't establish causality (and doesn't claim to), but the authors clearly think that NCLB and the standards movement in general is working: working in the sense that the bottom 10% on NAEP are steadily improving their achievement:

This is the first time I've seen the idea that NCLB is working supported by data.

It's also the first time I've heard that it's the bottom scorers, not the "bubble children" who are benefiting from NCLB.

A couple of things for now.

The report doesn't seem to mention the 1995 recentering of SAT scores or the fact that the decline in SAT scores was concentrated at the top. The report practically invites readers to shrug off the "needs" of the top 10% -- if they're already on top, how can they go higher?

Beyond this, I'm somewhat disturbed by the universal acceptance of the idea that "excellence" and "equity" are two separate things. Apparently the policy world is prepared to recognize only two conceivable positions:

- you can have equity or you can have excellence, but you can't have "both"

- you can have equity and you can have excellence; you can have "both"

The possibility that equity and excellence are flip sides of a coin isn't on the menu.

What I've seen, time and again, that if a school isn't doing a good job teaching the bottom 10%, it isn't doing a good job teaching the top 10%, either. It may look like it's doing a good job. But once you factor out the parent reteaching & the tutors, you see that ineffective teaching is ineffective teaching. Period.

I had started to wonder about this in terms of athletic programs. Often people think of athletics and academics as either/or -- and when you're talking about athletics and academics at the highest level of individual achievement, of course they are either/or.

But when you're looking at a school, what goes with what?

Good academics with poor athletics?

Good athletics with poor academics?

I'm coming to the conclusion that's not the case.

No time to give my various "data points" at the moment, so I'll content myself with just one.

Two weeks ago I attended the Sports Orientation Night at C's new school. The place was mobbed. The principal spoke first. Toward the end of this talk he said that 10 or 12 years ago, the school had decided to raise its admission standards. The one thing he regretted at the time, he told his wife, was that the school had always been known for its strong athletic programs. Once they started admitting more academically oriented kids with higher scores, their win-loss records would suffer.

But that's not what happened. Instead, the wins show up; in one year alone the school won 3 more citywide championships than they had in the preceding 7 years. The principal and the athletic director both said they still don't understand why that happened.

To me, it made sense. I'd been noticing that great high schools, academically speaking, tend to have great teams.

A school that's on the march is on the march. They're not on the march here, but phoning it in there. When you're on a mission, you're on a mission.

I understand that trade-offs exist, opportunity costs are real, etc. But I don't think "trade-offs" and "opportunity costs" capture the way a high-performing organization functions.

In fact, I'm sure of it.

Back later.

Paul has an opinion

Well here's what I make of this...

The 'teacher' is an unprofessional (jeans, untucked shirt, unkempt person) asshole, in love with the sound of his pomposity and pseudo intellectualism.

If my phone had been treated thusly the only thing that would keep me from the untold joy of making him eat the pieces of my dead phone would be the more profoundly enjoyable judgment I could get in civil court after having the judge watch this video.

Obviously, Paul is correct (unless that same person's cel phone had just gone off 10 times in a row prior to the cel-phone smashing denouement?)

The reason I myself had trouble reaching this conclusion is that Mr. Advanced Classes Pitchperson puts me in mind of J.R. Xxxxxxx, the 17-year old Sunday school teacher I had when I was in junior high who used to throw chalk at us. J.R. was well within his rights.

OK, maybe not well within, but he had a point.

At the time, I was shocked. Chalk-throwing? In Sunday school? Chalk-throwing by the Sunday school teacher? Plus, J.R. could whip that stuff; it was a scene I recall vividly to this day, which indicates Major Emotional Learning, in case anyone is wondering. That is to say, I remember J.R. throwing chalk as well as I remember the moment I learned that the first plane had hit the North tower.

In retrospect, a 17-year old teaching 12 year olds in Sunday school is obviously going to produce chalk-throwing. There's really no other possible outcome.

stagnation at the top

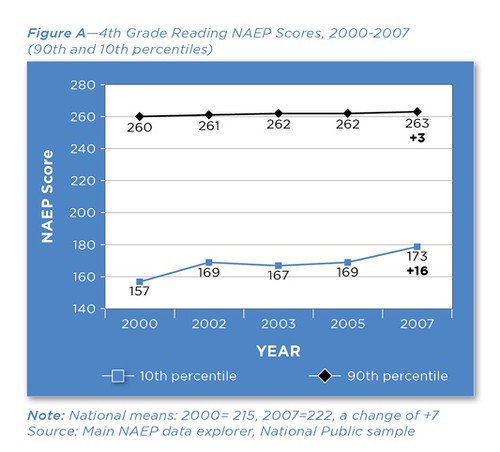

The report doesn't establish causality (and doesn't claim to), but the authors clearly think that NCLB and the standards movement in general is working: working in the sense that the bottom 10% on NAEP are steadily improving their achievement:

This is the first time I've seen the idea that NCLB is working supported by data.

It's also the first time I've heard that it's the bottom scorers, not the "bubble children" who are benefiting from NCLB.

A couple of things for now.

The report doesn't seem to mention the 1995 recentering of SAT scores or the fact that the decline in SAT scores was concentrated at the top. The report practically invites readers to shrug off the "needs" of the top 10% -- if they're already on top, how can they go higher?

Beyond this, I'm somewhat disturbed by the universal acceptance of the idea that "excellence" and "equity" are two separate things. Apparently the policy world is prepared to recognize only two conceivable positions:

- you can have equity or you can have excellence, but you can't have "both"

- you can have equity and you can have excellence; you can have "both"

The possibility that equity and excellence are flip sides of a coin isn't on the menu.

What I've seen, time and again, that if a school isn't doing a good job teaching the bottom 10%, it isn't doing a good job teaching the top 10%, either. It may look like it's doing a good job. But once you factor out the parent reteaching & the tutors, you see that ineffective teaching is ineffective teaching. Period.

I had started to wonder about this in terms of athletic programs. Often people think of athletics and academics as either/or -- and when you're talking about athletics and academics at the highest level of individual achievement, of course they are either/or.

But when you're looking at a school, what goes with what?

Good academics with poor athletics?

Good athletics with poor academics?

I'm coming to the conclusion that's not the case.

No time to give my various "data points" at the moment, so I'll content myself with just one.

Two weeks ago I attended the Sports Orientation Night at C's new school. The place was mobbed. The principal spoke first. Toward the end of this talk he said that 10 or 12 years ago, the school had decided to raise its admission standards. The one thing he regretted at the time, he told his wife, was that the school had always been known for its strong athletic programs. Once they started admitting more academically oriented kids with higher scores, their win-loss records would suffer.

But that's not what happened. Instead, the wins show up; in one year alone the school won 3 more citywide championships than they had in the preceding 7 years. The principal and the athletic director both said they still don't understand why that happened.

To me, it made sense. I'd been noticing that great high schools, academically speaking, tend to have great teams.

A school that's on the march is on the march. They're not on the march here, but phoning it in there. When you're on a mission, you're on a mission.

I understand that trade-offs exist, opportunity costs are real, etc. But I don't think "trade-offs" and "opportunity costs" capture the way a high-performing organization functions.

In fact, I'm sure of it.

Back later.

a pitch for advanced classes

I have no idea what to make of this.

I found it while attempting to Google the meaning of the phrase "drop toilet."

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

if you've time --

They're asking for comments.

I'm thinking of just cutting and pasting Anne Marie's comment and signing my name to it.

Speaking of the ASCD, Niki likes their smartbrief, which you can sign up for here.

Tuesday, June 17, 2008

focus, rigor, coherence

by William H. Schmidt

American Educator, Spring 2008

Why do some countries, like Singapore, Korea, and the Czech Republic, do so much better than the United States in math? I've heard all sorts of reasons; diversity and poverty top the list. But after some 15 years conducting international research, I am convinced that it's the diversity and poverty of U.S. math standards—not the diversity and poverty of U.S. students—that are to blame. The single most important result of the Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) is that we now know that student performance is directly related to the nature of the curricular expectations. I do not mean the instructional practices. I mean the nature of what it is that children are to learn within schools. (In the U.S., the curricular expectations are usually referred to as standards; in other countries they are known by various names.) ...The TIMSS research has revealed that there are three aspects of math expectations, or standards, that are really important: focus, rigor, and coherence. ...

Focus is the most straightforward. Standards need to focus on a small enough number of topics so that teachers can spend months, not days, on them. I'll just give you one illustration: in the early grades, top-achieving countries usually cover about four to six topics related to basic numeracy, measurement, and arithmetic operations. That's all. In contrast, in the U.S., state and district standards, as well as textbooks, often cram 20 topics into the first and second grades. That's much more than any child could possibly absorb.

Rigor is also pretty straightforward—and we don't have enough of it. For example, in the middle grades, the rest of the world is teaching algebra and geometry. The U.S. is still, for most children, teaching arithmetic. It's not rocket science: other countries outperform us in the middle and upper grades because their curricular expectations are so much more demanding, so much more rigorous.

Coherence is not quite as easy to grasp, but I believe it is the most important element. Coherent standards follow the structure of the discipline being taught. All school subject matter derives from some academic discipline, be it geography, history, mathematics, physics, etc. Once that formal academic body of knowledge has been parsed out and sequenced from kindergarten through 12th grade, it should reflect the internal logic of the discipline. This is especially important in mathematics, which is very hierarchical. Topics in math really need to flow in a certain logical sequence in order to have coherent instruction. If you look at the math curricula of top-achieving countries, you see a very logical sequence (which I describe in the sidebar on the right). The more advanced topics are not covered in the early grades. Now, that seems obvious—until you look at state and district standards in the U.S. Everything is covered everywhere. Far from coherent, typical math standards in the U.S. often appear arbitrary, like a laundry list of topics.

Thematic teaching cannot reflect the internal logic of the liberal arts disciplines.

Histogeomegraph is not a discipine.

Histogeomegraph is a mash-up.

trouble in paradise

Remember the mom who wrote about her 5th grade daughter entering KIPP?

Now she's going to meetings, emailing the Board, and finding teachers weeping in bathrooms:

Thanks for all your support on my ongoing KIPP struggle. The struggle continues, really nothing new to report, other than there are now 12 of 18 teachers who will not be coming back next year. I'm waiting for one of the Board members to get back in town and hopefully respond to some of my concerns. Reading your comments definitely helps me keep my determination to keep fighting. Thank you.I don't like the sound of some subjects will be combined.

So I went tonight to the KIPP meeting after all. I wasn't going to go. I was going to give myself the night off. I was going to spend the time with my Riley, while Sylvia's still away on her field trip. We were going to have a quiet evening at home.

Wouldn't you know, Riley said she wanted to go. My 7-year-old daughter wanted to spend her evening in a Board meeting. I've corrupted my child!

So we went. I did learn some things. But, unfortunately, not many of them were encouraging. I'm Chicken Little. I'm screaming at the top of my lungs that the sky is falling, and while they listen (and don't laugh), I don't feel like they hear me.

I just made one more effort, one more attempt. I wrote a 1,240-word email. And somehow that's not enough. Once that was done, all I wanted to do was blog. No wonder my 7-year-old is corrupted; I'm seriously disturbed.

I haven't eaten dinner these last 2 nights. I've been in meetings, and when I get home, my appetite has been thoroughly drained. I'm tired, but I can't sleep.

Tonight, I'm having some wine to go w/ my whine. I may have to qualify this as a BUI post.

So here's my main concern. Because screw it, I'm putting it out there.

I have no confidence in the woman who has been hired to replace our Principal. I don't feel like she gives a crap about our concerns. She's treated the teachers poorly. As of tonight, 2 of them still don't know if they have a job next year! As of tonight, 9 out of 18 teachers will not be returning next year. After tomorrow, that number could rise to 10. I personally know only 2 teachers that are returning next year, and only one of them will be my daughter's. I think.

I don't know what the changes will be in the curriculum. I've heard that some subjects will be combined, but when my daughter's in school for nearly 10 hours a day, I don't see the need. Nor do I know what she will be doing in the times she used to take certain classes.

That is a directive straight from the BLOB.

The edu-world's blind faith in wholeism really is something. Here's a typical Statement of Core Belief:

We decided to create a unit plan on ocean animals for many reasons. One reason is the fact that children could have a lot of fun learning this information. It is a topic that sparks a child’s interest and makes them want to learn more. Children need to learn more about ocean life and how that ocean life relates to us. Because the loss of life in the ocean can and will affect everyone in the world it is important for the children to have a general understanding of the life that lives in the ocean, even if they do not live near the ocean.Needless to say, this is not what is typically meant by "coherence." This teacher's Thematic Unit on Ocean Animals springs out of nowhere. It doesn't follow logically from what has come before, nor does it lead logically to what will come after. It simply appears, full-blown, sprung from the brain of Zeus.

In addition, this theme is being taught in many schools today and we felt that it was important for us as future teachers to understand that there are many subjects that could be taught using this general theme. The ideas using this theme are endless. Teachers should understand that children will feel that what they learn is important if it is relevant. Teaching subjects in isolation leaves the children feeling disconnected and bored with learning in general. Learning by using themes is a way to add some creativity and enjoyment to learning subjects. Students need to be actively learning and doing in order to grasp the concepts involved. These hands on activities will get the students involved and thinking critically about animals on land as well as those who live in the ocean.

Behold, children!

A thematic unit on ocean animals!

We have the universities to thank for this, I think. They got caught up in an interdisciplinary quest a while back, leading to the proliferation of programs ending in the word "Studies." Cultural studies was pretty much the apotheosis of interdisciplinarity, and we know how that turned out.

Interdisciplinarity at the college level is now a selling point in college promotion materials, and continues to have its adherents. (warning: If Robert Sternberg has his way, the middle school model will be coming to a college near you).

There are any number of problems with interdisciplinarity, all of which, for our purposes, can probably be boiled down to the observation that interdisciplinarity doesn't work:

For nearly a decade, I regularly start the semester by asking students in my upper-level interdisciplinary general studies seminar what distinguishes the sciences, social sciences, and humanities from one another. ... [F]ew can offer more than vague ideas of how they differ. Most can identify disciplines that typically fall under the sciences; the majority can situate psychology and sociology in the social sciences, but further categorization of disciplines eludes many of them, as do other distinctions about these areas of the liberal arts such as hallmark methodologies and primary objects of study.Having significant exposure to disciplines in the liberal arts in conjunction with a primary area of study is a distinctive feature of higher education in the United States. Every spring and fall for at least four years, students throughout the country have to consider fulfilling general education requirements in the sciences, social sciences, and humanities. But, for many, maybe most, their general education courses are blank slots to be filled by brief conscripted voyages into less familiar disciplinary waters. They graduate more well rounded, with more breadth of content, not just depth, but few leave with a conscious understanding of how scholarly inquiry is conducted outside of their major and how inquiry in the liberal arts illuminates timeless questions and pressing concerns of humankind. As undergraduates accept their diplomas and exit the stage, they leave with an inchoate awareness of what they have been a part of.

In teaching upper-level interdisciplinary general studies seminars I also have observed that my soon-to-be-graduates struggle mightily when they engage in scholarly thinking themselves. Specifically, they have difficulty forming an intellectual thesis that goes beyond the obvious and supporting it with scholarly evidence, a formidable task. When writing papers or giving presentations, the majority of students unwittingly inhabit the lower realms of epistemological taxonomies. To situate their position in terms of two well-established schemas of educational development, my students are generally more comfortable being asked to recall and comprehend knowledge, the first rungs in Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956), as opposed to being asked to apply, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate knowledge, the higher end of this taxonomy....

Fortunately, students are called upon to reach these upper realms of thought in their major discipline, perhaps many times but particularly in capstone courses, such as senior seminars. The challenge is to do likewise in a capstone general studies course, particularly when such a course is interdisciplinary. However, the extent to which undergraduates can engage in, not simply learn about, interdisciplinarity is uncertain. Some academics who contemplate pedagogical issues, including Howard Gardner, renowned Harvard professor of cognition and education, wonder whether students in undergraduate education have enough disciplinary knowledge to do genuine interdisciplinary thinking (2006, p. 73). In his recent book, Five Minds for the Future, Gardner considers:

"And what of genuine interdisciplinary thought? I consider it a relatively rare achievement, one that awaits mastery of at least the central components of two or more disciplines. In nearly all cases, such an achievement is unlikely before an individual has completed advanced studies" (p. 77).

"Interdisciplinary" courses in middle school aren't interdisciplinary.

Thematic teaching isn't interdisciplinary.

The only people who can actually do interdisciplinary projects -- let alone interdisciplinary teaching -- are people who are expert in more than one discipline, and there are about five people like that on the planet:

We have an enduring fantasy of a grand, unified theory of knowledge in which each discipline contributes building blocks to a seamless edifice. How can we know the ways we are unified if we don't talk to one another?What we see in practice, however, when broad categories like the sciences, humanities, and social sciences are supposedly bridged, are a lot of courses on "Women and Health" or "Shakespeare and Art." Those are billed as interdisciplinary, and they are if you consider that an English professor who has some interest in visual arts is teaching the latter or a historian who has read about the history of medicine is teaching the former. But such courses aren't really interdisciplinary because both are taught by people trained in one discipline who are essentially amateurs in the other.

Can one person ever be a master of two trades? A little knowledge can be a dangerous thing, but a lot of knowledge can be even more dangerous. Careering off in varying directions isn't what our current educational system is about. After all, it takes a lifetime to learn a single discipline. In English, for example, to be expert you have to read a vast body of literature over a long period of time. If a physicist decides to teach an interdisciplinary course on literature and cosmology, will she really be proficient in both fields? Or if I decide to venture into medicine or science, will I have the training of a scientist or a physician? Obviously not.

A Grand Unified Theory of Interdisciplinarity

by Lennard J. Davis

Chronicle of Higher Education

June 8, 2007

These voices will not be heard. Even Howard Gardner, a man who has now written an entire book arguing that K-12 schools should devote themselves to teaching the disciplines, not the interdisciplines, will not be heard.

nope

Instead, we'll be hearing from the likes of Tom Friedman and Daniel Pink:

Pink: Once again, it goes back to integration. Or what I’ve called symphony, which is the ability to fit the pieces together.

Friedman: Absolutely. My friend Rob Watson — a great environmentalist who founded the LEED building concept — Rob likes to say that integration is the new specialty. The generalist is really going to come back. The great generalist — someone who has a renaissance view of the world — is more likely to spark an innovation than the pure engineer.

Pink: Let’s take this to the people who are reading this interview — school superintendents and administrators. Right now we frog-march kids from math to science to English — and too rarely make the connections among the disciplines. In your travels have you seen any examples of a smarter approach?

Friedman: I’ll give you one of my favorite examples: Rainforest Math. There’s so much one can learn from the laws of nature — not just biology, but Einstein, Newton, physics. And you drive both environmentalism and you drive math. So it’s those kinds of intersections that are going to produce the most innovative students.

Pink: So how do we bring that into the system? There’s team teaching, integrating the arts into the curriculum, writing across subject areas. What else?

Friedman: I think you’ve got to force it a little like Georgia Tech did and say: “You are going to study computing, and you are going to study screenwriting.” Then the assignment in the class is: Write an online play with what you’ve learned.

Pink: That makes sense. Instruction in the subject matter areas, but then leave the execution to the students. And give them a fair amount of autonomy along the way.

Friedman: Right. The assignment can be: “Mash these two together.”

Pink: And these kids get mash-ups.

Friedman: Oh, they get mash-ups. They do it naturally. And today, he who mashes best will mash most and be wealthiest.

Pink: Which country is the best masher on the planet?

Friedman: Oh, we are still. It’s not even close.

Tom Friedman on Education in the 'Flat world'

The School Administrator

February 2008

Tom and I see eye to eye on that one. When it comes to mashing up the liberal arts disciplines, American public schools lead the parade.

comments on "Knowledge School"

from Paul B.:

All of these isolated success stories seem to have a common thread. Kids go at different (appropriate) speeds. Kids have clear goals. Kids are measured against those goals. The teaching is directed. The focus is restricted to academic excellence not extracurricular social reengineering.

Makes me go hmmmmmm?

Note the technology creeping into this Swedish example. I'd bet that Kunskapsporten is a DI engine. I'd bet that kids are being taught in their 'zone'. Betcha' can make money at this on the $153K per teacher being spent in the U.S. of A.

from Allison:

It does definitely sound like Paul's model for technology that adjusts to rates, and it definitely sounds like they have some actual instruction behind it. I wish we could see the courses, to know what the instruction consists of, and what the assessment looks like. Anyone know anyone in Sweden?

le radical galoisien:

This looks promising -- but of course I want to know how these students compare with other students who aren't in the voucher programme.

former KS student:

Kunskapsskolan has a demo on its Swedish website, where you can at least get a feel for what the portal looks like:Thank you, former KS student! (tell us more, if you have time)

As for results, statistics from 2007 show that Kunskapsskolan performs significantly better than the national average in English and Swedish. 2008 figures are expected to show a similar advantage in Maths as well.

Ben Calvin:

I assume something's been lost in translation with the "better to do things the same way than to do them well" line ?

I don't think so. It's a pretty common statement when talking about standardizing anything. If you do something the same way, you know how it's being done. There may be a better way, but it needs to be implemented across the board, and not just one person (or teacher) doing something different than what the system assumes.

I went to the Sports Orientation Night at C's new school last week.

wow

We are entering a different world. It's as if we're shipping C. off to Hogwarts. The new school feels magical, and I call myself blessed that my Muggle child will be allowed to attend.

I bring this up here because of Paul's comment about social re-engineering.

At the moment, I suspect that great schools often do have an element of "social engineering," or something akin to it, but I don't know how to describe what they do.

The Sports Orientation Night was all about character & culture. You ktm-ers will love this: "We play to win." That is a Major School Value. "We play to win, but academics come first." I must have heard that about 10 times over the course of 45 minutes.

I suspect that really good schools have a mission.

A new friend of mine, here in town, sent an email a while back saying that the more closely involved with religion a school is, the better that school will be. What he meant wasn't that good schools are churches. He meant that schools run by churches are better than schools not run by churches.

I had never heard that before. Never heard it; never thought it, although I did know something about the research on urban Catholic schools.

Nevertheless, his observation made immediate sense.

Why?

Because a school run by a church is likely to have a mission.

John (Ratey) used to talk about that all the time. Kids need a mission, he said. Parents, too. Everybody needs a mission.

Well, parochial schools have a mission. By definition. So do KIPP schools. So do many of the new urban charter schools. With public schools, it's harder. There are so many constraints on a public school, so many competing interests. I think a public school can have a mission - from afar, I would say that the schools Karen H's kids have attended have a mission. (The Race Between Technology and Education explains why, btw.)

And, of course, within any public school you always find teachers who have a mission.

But a teacher with a personal mission is different from an institution with a mission.

The school mission seems always to involve character and culture, but that's about as far as I've gotten with this line of thought.

Steve Levitt summarizes The Race in 2 sentences

Jimmy graduates

The anemic response of skill investment to skill premium growth

The declining American high school graduation rate: Evidence, sources, and consequences

Pushy parents raise more successful kids

The Race Between Education and Technology book review

The Race Between Ed & Tech: excerpt & TOC & SAT scores & public loss of confidence in the schools

The Race Between Ed & Tech: the Great Compression

the Great Compression, part 2

ED in '08: America's schools

comments on Knowledge Schools

the future

the stick kids from mud island

educated workers and technology diffusion

declining value of college degree

Goldin, Katz and fans

best article thus far: Chronicle of Higher Education on The Race

Tyler Cowan on The Race (NY Times)

happiness inequality down...

an example of lagging technology diffusion in the U.S.

the Times reviews The Race, finally

IQ, college, and 2008 election

Bloomington High School & "path dependency"

the election debate that should have been