College-educated workers are more plentiful, more commoditized and more subject to the downsizings that used to be the purview of blue-collar workers only. What employers want from workers nowadays is more narrow, more abstract and less easily learned in college.To be sure, the average American with a college diploma still earns about 75% more than a worker with a high-school diploma and is less likely to be unemployed. Yet while that so-called college premium is up from 40% in 1979, it is little changed from 2001, according to data compiled by Jared Bernstein of the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal Washington think tank.

Most statistics he and other economists use don't track individual workers over time, but compare annual snapshots of the work force. That said, this trend doesn't appear due to an influx of lower-paid young workers or falling starting salaries; Mr. Bernstein says when differences in age, race, marital status and place of residence are accounted for, the trend remains the same.A variety of economic forces are at work here. Globalization and technology have altered the types of skills that earn workers a premium wage; in many cases, those skills aren't learned in college classrooms. And compared with previous generations, today's college graduates are far more likely to be competing against educated immigrants and educated workers employed overseas.

The issue isn't a lack of economic growth, which was solid for most of the 2000s. Rather, it's that the fruits of growth are flowing largely to "a relatively small group of people who have a particular set of skills and assets that lots of other people don't," says Mr. Bernstein. And that "doesn't necessarily have that much to do with your education." In short, a college degree is often necessary, but not sufficient, to get a paycheck that beats inflation.

Economists chiefly cite globalization and technology, which have prompted employers to put the highest value on abstract skills possessed by a relatively small group, for this state of affairs. Harvard University economists Lawrence Katz and Claudia Goldin argue that in the 1990s, it became easier for firms to do overseas, or with computers at home, the work once done by "lower-end college graduates in middle management and certain professional positions." This depressed these workers' wages, but made college graduates whose work was more abstract and creative more productive, driving their salaries up.

Indeed, salaries have seen extraordinary growth among a small number of highly paid individuals in the financial sector -- such as fund management, investment banking and corporate law -- which, until the credit crisis hit a year ago, had benefited both from the buoyant financial environment and the globalization of finance, in which the U.S. remains a leader.

Richard Spitzer is one of those beneficiaries. He received his undergraduate degree in East Asian studies in 1995 from the College of William and Mary and graduated from Georgetown University's law school in 2001. The New York firm for which he works, now called Dewey & LeBoeuf, has a specialty in complex legal work for insurance companies. There, Mr. Spitzer has developed an expertise in "catastrophe bonds." An insurance company sells such bonds to investors and pays them interest, unless an earthquake, a hurricane or unexpected surge in deaths occurs.

Experts in these bonds are "probably a rarefied species -- there's only a few law firms that do them," says Mr. Spitzer, 35 years old. He typically spends two to four months on a single deal, ensuring that details like timing of payments or definition of the triggering event are precise enough to avoid disputes or default.Mr. Spitzer's salary has doubled to $265,000 since joining in 2001, in line with salaries similar firms pay.

But not all law graduates are so fortunate; many, especially those from less-prestigious schools, have far lower salaries and less job security. Similarly, some computer-science graduates strike it rich. But their skills are not as rare as they were in the early 1980s, when the discipline took off, and graduates today must contend with competition from hundreds of thousands of similarly qualified foreign workers in the U.S. or overseas.

The Declining Value of Your College Degree

in a nutshell:

(entire article posted here)

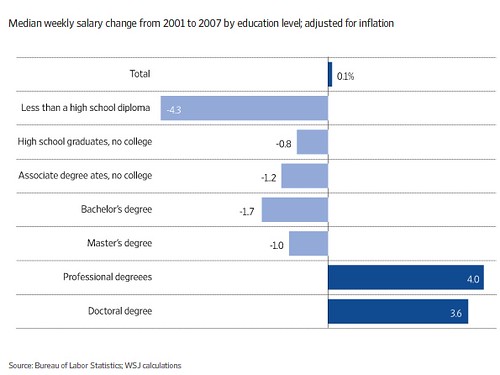

- the returns to a Bachelor's degree dropped between 2001 & 2007

- the returns to advanced degrees increased between 2001 & 2007

The rising inequality described in this article is the subject of Goldin & Katz's The Race Between Education and Technology. Their explanation, however, is quite different in substance and in emphasis.

Goldin & Katz's book isn't about the horrors of globalization. It is so not about the horrors of globalization that the word globalization doesn't even appear in the index.

The word outsourcing appears once:

Even though international outsourcing has been blamed for the decreased utilization of the less educated, the facts in this case argue against that explanation as being the primary factor. Large within-industry shifts toward more skilled workers occurred in sectors with little or no foreign outsourcing activity, at least in the 1980s and up to the late 1990s. (p. 98)

Goldin and Katz document and analyze a race between eduction and technology. As technology advances, the demand for educated workers advances, too. This has been true since the end of the 19th century.

(Prior to that, advancing technology reduced the demand for skilled labor, as when the invention of factories reduced the demand for skilled artisans.)

The law of supply and demand determines wages. For 75 years, American public schools created a continuously increasing supply of educated workers, more than any other country in the world. Because we produced so many educated workers, income inequality steadily fell.

That changed in 1980. We are no longer seeing enormous gains in educational attainment from one generation to the next. It used to be that kids were always much more educated than their parents; those days are gone.

Meanwhile, the advance of technology has not slowed. We are producing more high-level jobs, and fewer high-level workers. This means the highly educated earn more while others earn less.

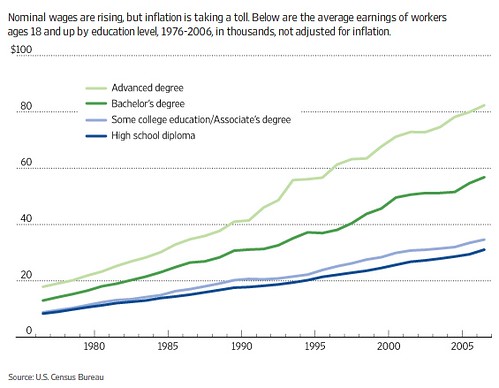

The two charts below accompanied the WSJ article:

The second chart is the important one. This chart goes back to 1976. Look how close the lines are in 1976. The difference between a lawyer and a plumber back in the day wasn't that big. I'm old enough to remember that time. Newspapers and magazines were filled with articles arguing that college wasn't worth the money because you could get rich being a really good plumber.

Then look at the difference between a plumber and a lawyer today.

Winner take all.

Given the (apparently) related fact that we also see rising within group inequality, I see two rational responses:

- do everything in your power to see to it that your kids receive a superb education up through graduate or professional school

- carry on lobbying schools & governments to fix the schools, which, in my case means supporting charters & vouchers as well as school reform

Steve Levitt summarizes The Race in 2 sentences

Jimmy graduates

The anemic response of skill investment to skill premium growth

The declining American high school graduation rate: Evidence, sources, and consequences

Pushy parents raise more successful kids

The Race Between Education and Technology book review

The Race Between Ed & Tech: excerpt & TOC & SAT scores & public loss of confidence in the schools

The Race Between Ed & Tech: the Great Compression

the Great Compression, part 2

ED in '08: America's schools

comments on Knowledge Schools

the future

the stick kids from mud island

educated workers and technology diffusion

declining value of college degree

Goldin, Katz and fans

best article thus far: Chronicle of Higher Education on The Race

Tyler Cowan on The Race (NY Times)

happiness inequality down...

an example of lagging technology diffusion in the U.S.

the Times reviews The Race, finally

IQ, college, and 2008 election

Bloomington High School & "path dependency"

the election debate that should have been

26 comments:

If you're a plumber with your own business, you can make a lot! If you're just a plumber working for a plumbing business, you don't make much. I know, my folks live next to a plumber who owns his own business. Also, the last plumber that came to our house worked for a company, he said he didn't make much compared to what I paid! I told him about my neighbor and told him he needed his own plumbing van and his own business, he seemed like a smart enough guy to run his own business.

I'd love to see figures on independent businessmen.

"The Race" shows that there are increasing premiums to education across the board -- for farmers, plumbers, everyone.

Actually, my dad is a perfect example. He was highly educated for his day, and he did extremely well as a farmer.

He was one of those early adopter-types. He read all the Extension magazines on hybrid seed corn, etc. In the winter he used to work for Extension doing all the other farmer's books.

The separations between lines are bigger, but you've also got to be careful with plots like this. Arguably, what matters in relative salaries is the ratio not the difference, since much of the absolute increase in wages is a function of inflation, which isn't considered here.

By my rough math, the ratio of Advanced Degree salaries to High School diploma salaries was ~2.1 in 1976 and ~2.5 in 2006. That's an increase, but isn't as much of an increase as you might have guessed just eyeballing the graph. The Advanced/Bachelor's degree ratio was ~1.4 in 1976 and ~1.4 in 2006! You can see this if you compare the relative gaps between the top line, the middle line, and the bottom line -- the total amount of the gap increases, but the relative gaps (above and below the green line) are about the same.

Sorry to be picky, but if we're going to talk about math...

This article touches upon a notion I've had for some time now; namely, that "everybody needs a college education" is one of the biggest myths going around. The law of supply and demand works on college degrees like it does everything else, so it stands to reason that the more commonplace college degrees are, the less they are worth. Consequently, a BS/BA is the new high school diploma: employers use it more as a screening tool than anything else. A master's is essentially the equivalent of what a bachelor's was 40 years ago.

This decline has gone on for quite a while. My father graduated from a technical high school in 1938; considering the subjects he studied there, I would be willing to posit that his H.S. diploma was the equivalent of a bachelor's some 40 years later.

Another reason that I believe that it's false and misleading to insist that a college education is the "right thing" across the board is because you can't get around the fact that not everyone is college material. Some kids simply aren't interested, and (to put it bluntly), some simply aren't smart enough. We do these kids a disservice by insisting they go to school and rack up a ton of debt when the chances are that they'll drop out before getting a degree. Plus, letting anyone, regardless of ability, get a college degree cheapens the whole system by pandering to the lowest common denominator.

Arguably, what matters in relative salaries is the ratio not the difference, since much of the absolute increase in wages is a function of inflation, which isn't considered here.

sorry --- I should have posted that. They've got a chart showing the increasing ratio, too.

"The Race" spends a great deal of time on the increasing ratio between skilled & less skilled labor. That ratio has been steadily increasing since 1980.

wordsmith

right, exactly -- a college degree is roughly now what a high school degree used to be (I may be overstating or understating that; I'll check)

I suspect that the idea that not everyone is college material is probably wrong. We don't know what the ceiling on learning is, and we base our assumptions on what we've lived with, which is public schools that have declined in quality over the years.

In France, the Baccalaureate degree, which I think most kids get & which we think of as equivalent to a high school degree, is the equivalent of the first two years of college.

What Goldin & Katz show -- this is one of the most startling restuls of the book for me -- is that the increasing returns to education aren't just about credentialing or signaling. Across the board and for many decades now (probably for the past century), companies that hired more highly educated workers were more successful in their business, regardless of what their business was.

I'll get some of that material posted later on.

As for the issue of how people who aren't all that interested in school will get through, that was also an issue when high schools were being invented. Progressive educators all agreed that not everyone could learn academic subjects in high school, but they were wrong.

My perception is that Vicki Snider is right: we're going to need a "science of teaching" and we're going to need it soon.

If the country is going to educate more and more people to a higher and higher degree, the teaching is going to have to be extremely good. In other words, we're going to have to know how to teach advanced subjects to people of average intelligence and below.

Other countries are doing this now, at least at the high school level.

That's why Singapore kids are so far ahead of ours.

I suspect that the idea that not everyone is college material is probably wrong. We don't know what the ceiling on learning is, and we base our assumptions on what we've lived with, which is public schools that have declined in quality over the years.

True; I base my opinion upon the present system, since that's all we have available. I'm sure that there are those students that could do better if they applied themselves, especially if they were given practical study skills and things like that. But on the other hand, there are some students that seem to be beyond any type of academic help, and it is this group of students whose ability to complete a rigorous college career I question.

Case in point: I currently have a student ("student A") in a remedial (*basic* algebra) class, who is supposedly LD and therefore, under college policy, entitled to as much extra time as needed to complete exams. So, after the allotted class time, I send A down to the testing center to finish the test. Setting aside the issues of mastery and fairness, with all that extra time, A still manages to get a grade no higher than a "D." Furthermore, in ordinary conversations, A seems to zone out more often than your average college student - straightforward answers to routine questions (let alone questions regarding homework) generally elicit a what-language-are-you-speaking-can-you-repeat-that look.

Is A as dumb as a box of rocks? I don't know, but based on what I've seen so far, I really can't envision A successfully completing college. How many students are there like A? Again, I don't know, but is it fair to A to hold out hopes of getting a college degree that is actually worth something? And if A is allowed to get a degree in basketweaving just for the sake of getting a "college education," is it fair to students who major in something like engineering, math, or physics and have therefore earned their degree? Then even reputable colleges are in danger of sinking to the level of a diploma mill.

Everyone has to have a college degree these days precisely because college is becoming the new high school. For most colleges I suspect this is a reluctant transformation. They don't want to be the new high school but are being forced into it because of the unpreparedness of their incoming students.

If the college education of today is akin to the high school education of yesteryear, then yes, it follows that everyone is "college material."

It also follows that the workforce will appear to be better educated as time goes on simply because the highest degree attained becomes higher...but how can one tell if the people are better educated, or if instead the value of the degree has been deflated?

This is a terrible state of affairs! People who should be ready to work at age 19, after a high quality and *free* public education, are now forced to put their work lives on hold, take 4 more years of school that might not interest them, and rack up tons of debt.

I resist the "college for all" solution to this problem. We should focus on fixing the K-12 system and shoring up the colleges as merit-based institutions. Getting into, and graduating from, a college should remain a real achievement. This does not imply an impenetrable ceiling, but it does imply that some people will need to work hard to succeed at that level.

Sorry if I sound elitist; I don't mean to. To the contrary, I would like to see a high school education for every student that prepares them for strong careers without the need for college. Then, college can become once again optional, ready and waiting for that subset of students who want to become engineers, scientists, historians, and the like.

One of the biggest problems on college campuses these days is student disengagement. No surprise! Years ago, most kids were there becuase they wanted to be there; now they are there because they *have* to be there, and they are paying more $$$ than ever for the "privilege." Check out the website and book Ivory Tower Blues for more thoughts along these lines. And after 13 years in our K-12 system, can you really blame them for being academically disengaged? I often wonder what would have become of myself as a student in the current educational environment. I really liked school and I was excited about college. But if I were in school today, instead of ending up with multiple higher degrees, I'm not really sure I would have had the patience to make it out of high school.

vickys: What you said.

FWIW, I don't think it's being elitist, any more than it's elitist to say "We have certain standards, and if you want to join with us, you'll have to meet our standards." By that definition, everyone would be "elitist" in one way, shape, or form.

"I suspect that the idea that not everyone is college material is probably wrong."

Catherine, *half* the population has an IQ less than 101. I suspect that you don't spend much/any time during a normal day with this 1/2 of the population.

-Mark Roulo

hah!

That's where you're wrong.

I have two kids whose measured IQs are well below 100. (Actually, I don't know about Andrew --- haven't asked.)

Seriously, though, we don't know what the ceiling is. People said the same thing back when the high school movement was happening. People with below-average IQs couldn't be expected to learn algebra.

I interviewed Irving Gottesman years ago; he explained it to me best. He used the idea of the "range of reaction," which I gather is still more or less on target.

IQ is a range; it's not a point.

Education makes you smarter; it raises your IQ. I assume education does that by moving you to the top of your "reaction range," which iirc Gottesman said was a full 40 points.

Our public schools aren't even coming close to moving kids to the top of their ranges -- at least, not in my experience.

Public schools can also lower IQ. (The fact that school raises and/or lowers IQ is well-documented as I understand it. I'm not just expressing an opinion.)

My favorite example, though, is Alex the Parrot. Until Irene Pepperberg came along, no one had been able to teach birds anything. Birds don't have frontal lobes; experts assumed that birds really were "bird brains."

When he died, Alex the parrot had achieved the cognitive level of a 4 to 6 year old child. I assume his true cognitive level was far higher than that.

Goldin & Katz, comparing US educational attainment to Europe's, say that we haven't reached the ceiling -- I'll get some of that material posted.

The other issue is that I don't think we know that much about how IQ relates to knowledge. As far as I can tell, a lower IQ means slower learning -- I'm not clear that a lower IQ means that more advanced topics are off limits.

The way things stand, we've based our opinions of what people are capable of learning on what people are capable of learning in the education system we have.

We have no idea what the ceiling would be if Siegfried Engelmann were in charge of curriculum & teaching.

Is A as dumb as a box of rocks? I don't know, but based on what I've seen so far, I really can't envision A successfully completing college. How many students are there like A?

Seems like there are A LOT OF STUDENTS JUST LIKE A.

The problem is, we're assuming that this situation is natural: that As flaws are an essential feature of A, rather than a feature of A who has spent 13 years in the public school system.

I'm telling you: I have watched, with my own eyes, very bright children become "dumb."

I've seen it.

When kids fail over and over and over again....they change completely.

From afar, my diagnosis of "A" is that he shouldn't be in your class at all. He needs to back WAY up and take 3rd grade math, probably.

And if A is allowed to get a degree in basketweaving just for the sake of getting a "college education," is it fair to students who major in something like engineering, math, or physics and have therefore earned their degree? Then even reputable colleges are in danger of sinking to the level of a diploma mill.

Right, but that's a separate issue (though not an unrelated issue, obviously).

What The Race and work by other economists show is that high school degrees & college degrees aren't just a signaling mechanism; we're not talking only about a form of credentialism.

A person who has attended a diploma mill will do far worse economically than a person who has attended a good college.

This is a terrible state of affairs! People who should be ready to work at age 19, after a high quality and *free* public education, are now forced to put their work lives on hold, take 4 more years of school that might not interest them, and rack up tons of debt.

I agree --- but I see the solution differently.

I would make K-12 education radically more efficient; I wouldn't have kids spending 13 years of their lives in K-12 and ending up with algebra 1 & some geometry as I did (and as lots of kids are doing now).

Someone left a Comment about the exact number of years kids in Singapore attend school --- I think it's from ages 6 to 16 (correct me if I'm wrong).

In those 11 years those kids, including the kids with below-average IQs, learn far more than the vast majority of our kids do.

Remember that colleague of Ed's who said that when he spent a year in France on an exchange program he was put in the "slow girl" math track?

That guy has an IQ well above average; presumably the girls in the class had IQs that were below average.

The issue is that jobs are growing steadily more intellectually demanding. This has been happening for 100 years now, though I suppose it could change.

That's actually a question I have: is there a ceiling on how advanced the level of knowledge necessary to perform newly created jobs can be?

Will 100 years of steady, continuous growth in the complexity of knowledge required to perform existing jobs level off at some point?

I don't know what to think about that.

And after 13 years in our K-12 system, can you really blame them for being academically disengaged? I often wonder what would have become of myself as a student in the current educational environment.

I feel exactly the same way.

It's a big question for me.

We need a "science of teaching" as Vicki Snider says, which would encompass a science of motivation; we need highly efficient, highly effective education that doesn't burn kids out.

Ed read the Hirsch piece this morning - "Romancing the Child."

He'd never read it before & he had the same reaction I did: once you really grasp the fact that constructivism is a form of religion growing out of the romantic period, which involved a transfer of religious belief from God to nature, you see that there is simply no way out of this conflict.

If you think drill and kill is drill and kill, then when the state tells you your kids' scores have to rise, that's what you'll do. Joyless drill and kill.

People who think learning and practice are good things will find ways to create drill and thrill (sorry - that's corny); you'll have the KIPP folks teaching their students rap poems for math facts & creating a longer schedule so there's more downtime, etc.

As things stand, our public schools are set up to use projects, which would burn me out if I were a kid, or drill and kill, which would also burn me out if I had to use drill and kill to learn subjects through calculus, physics, and AP lit & history.

once you really grasp the fact that constructivism is a form of religion growing out of the romantic period, which involved a transfer of religious belief from God to nature, you see that there is simply no way out of this conflict.

I don't know, I'm not convinced that most teachers and administrators are operating out of a truly, deeply held faith in the principles of constructivism.

It seems more likely to me that many if not most believe in constructivism at least partly because it is in their political interests to do so--though it's not necessarily happening on a conscious level.

Why do you say political interests?

(I'm not challenging the statement -- just don't quite know what you're getting at.)

I should qualify my comment: "religious belief" applies to the ed school level -- I've seen it apply to administrators, too.

I wonder how many teachers are "true believers."

Teachers are in the trenches.

btw, I don't use the phrase "true believers" to be insulting, though I realize it sounds insulting.

At some point this year, I realized that I have a religion of education myself, which is that I believe in the liberal arts. Period. It's not just that I think the liberal arts are useful to know, that a good education in the liberal arts makes you a faster learner down the road and gives you cultural literacy & so on ----- I profoundly value the liberal arts and the content taught in a classical education.

You could hand me a whole raft of empirical studies showing that people who construct their own meaning while reading Oprah books and DIGG earn big bucks, marry well, & live longer, & it wouldn't matter.

We're in the realm of core values, and you can't disprove core values with studies.

Last but not least....the word "religion" isn't right for what I'm talking about; Hirsch uses it much more precisely, and traces the development of progressive ed ideas from the romantic period.

I probably don't have a "religion" of classical education, strictly speaking.

But I do have a core value that isn't open to question or discussion.

Why do you say political interests?

Oh, I just meant "political" in the sense of staying on the right side of those who are in power.

I'd be curious to read more about how you see the role between the ed school profs, the administrators, and the teachers in the trenches. Basically, how the "religiosity" aspect interacts with the power structure.

Incidentally, I didn't think you were being dismissive of "true believers", and I hope I didn't sound like I was being dismissive.

Mostly, I'm trying to stay optimistic about working within the current system, as someone who both has young kids about to go through public school (one about to start 1st grade, one still in nursery school) and as someone working to get certified to teach elementary school.

I'm still chewing on a lot of this. I should read the Hirsch piece.

Oh, I just meant "political" in the sense of staying on the right side of those who are in power.

I sense that is a part of it, also. The edu-jargon that most teachers and administrators use would be a clue to any recruit about what they should believe.

SusanS

Oh, I just meant "political" in the sense of staying on the right side of those who are in power.

Oh!

Yes, of course.

That would have to be part of it.

I'm sure there are tons of teachers who aren't particularly sold on any of this, and who are fed up with the chronic churning of curricula, programs, etc.

I'd be curious to read more about how you see the role between the ed school profs, the administrators, and the teachers in the trenches. Basically, how the "religiosity" aspect interacts with the power structure.

As far as I can tell, the ideologues (and I do mean that term pejoratively!) are ed school professors & administrators, rarely teachers (if I'm wrong folks should let me know). Apparently teachers use the phrase "in the trenches" to distinguish themselves from administrators (especially "central administrators) & I think that's exactly right.

The first time I saw a teacher blogger make that distinction, it struck that it explains why ktm has parents and teachers -- both groups are in the trenches. Both parents and teachers are living all these top-down Implementations and Innovations and 21st Century Improvements here on the ground.

Incidentally, I didn't think you were being dismissive of "true believers", and I hope I didn't sound like I was being dismissive.

Oh, no -- not at all!

Mostly, I'm trying to stay optimistic about working within the current system, as someone who both has young kids about to go through public school (one about to start 1st grade, one still in nursery school) and as someone working to get certified to teach elementary school.

boy....

I've given up, BUT I have to say that I do know good public schools. Karen H's schools are obviously terrific.

I also think elementary schools are radically better than middle schools, and may be radically better than most high schools, too.

High schools have the challenge that by the time kids get there they've got massive gaps in knowledge, etc.

Romancing the Child is a terrific piece to read.

It find it incredibly helpful to know where an idea came from, what its roots are.

The other important thing to remember is that everyone believes romantic ideas to some extent.

Ed schools have taken them to the limit, but you're going to have to look far and wide to find an American who doesn't reflexively think the "natural" is better than the "artificial."

I reflexively prefer "the natural" myself.

Thanks, Catherine, your comments explain a lot.

I'm reading the Hirsch essay and putting some thoughts together.

Let us know!

I'll go ahead and post the sections from Isaiah Berlin's famous book on romanticism. (I know it's famous because I read that it's famous, not because I've read the book myself...)

Ed says there's a fantastic textbook on intellectual history, which is obviously another subject I need to know.

I'll get the title.

Post a Comment