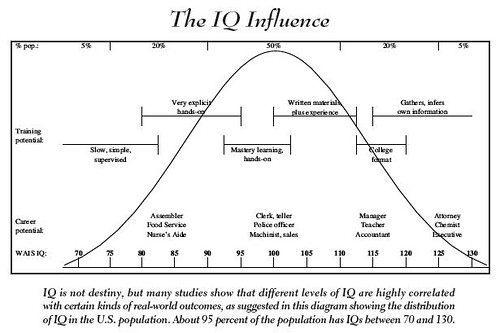

The legend reads:

IQ is not destiny, but many studies show that different levels of IQ are highly correlated with certain kinds of real-world outcomes, as suggested in this diagram showing the distribution of IQ in the U.S. population. About 95 percent of the population has IQs between 70 and 130.

The 6 training modes, from left to right, are:

- slow, simple, supervised

- very explicit, hands-on

- mastery learning, hands-on

- written materials, plus experience

- college format

- gathers, infers own information

Schools and the g Factor (pdf file)

The Wilson Quarterly

Summer 2004, page 38

Linda Gottfredson homepage

The General Intelligence Factor (pdf file)

by Linda Gottfredson (1998, Winter)

Scientific American Presents

(9)4, 24-29 1998

___________________

good schools raise IQ, bad schools lower IQ, part 1

good schools raise IQ, bad schools lower IQ, part 2

good schools raise IQ, bad schools lower IQ, part 3

the g Factor curve

21 comments:

I would interpret the traing potentials as the level of training that could at mimimum teach someone how to perform a task.

Just because someone in the 130 range is capable of figuring it out themselves, doesn't mean that the best way to teach them is to just give them the goal and leave them alone.

"Gardner’s theory has been protected from direct contradiction by his failure

to develop any formal tests of his proposed intelligences."

I liked this quote. This is true for most ed school ideas.

I have mentioned before that our public schools sent home a questionnaire asking parents how their kids learn. One parent had the nerve to return the form and say "fast".

A serious discussion of IQ can perhaps change the educational philosophy of schools, but I doubt it. The assumtion is that there is some process for change that includes rational thought. I don't think a critical mass is possible.

I was going to blog on this, but I have a headache so I will throw out the reference here.

From the conclusion of Time, Equality, and Mastery Learning by Marshall Arlin

"…I suspect many North American educators are incensed by the social inequalities they see about them, and are oppose to programs that hint at elitism, or that seem to perpetuate these inequalities. I suggest that the notions of inequality among students and differences among students are sometimes perceived interchangeably. I suspect that many teachers would like to oppose hereditarian or stable differences positions with an environmentalist position…"

"…But educators, and particularly teachers, are faced with individual differences among students. Not only do these differences remain stable as they appear to in this review, but they often seem to increase with each year of schooling…"

"…Rather, collective leveling functions as an unconscious means to establish an equilibrium between the apparently conflicting ideals of equal time and equal achievement (equal opportunity and equal outcomes) amid the pervasive background of individual differences. By providing more time that the majority of students need, schools can move students toward a lower common denominator…"

It is an excellent review of literature about the paradox of equal results vs equal time of mastery learning.

Sorry, forgot to add. The above quotes refer to why teachers don't use mastery learning techniques.

If they did, either they would have to devote much more time to slow learners, leaving fast learners waiting around or they would provide equal time to everyone, resulting in fast learners accelerating their learning so quickly that it would magnify the differences.

Educators are caught between reality rock and their hard place.

They know that some kids are smarter, by definition, if you will. They may like to pretend that all kids have their own strengths (intellegences), but they know that there is something else going on. They see it in class everyday. However, to get their "hard" view of education to work with reality, they have to do a lot of pretending, like pretending that smart kids are really not so smart.

The head of curriculum at our public schools told me once that kids come into Kindergarten at many different levels, but by fourth grade, most of the differences level out. I felt like telling her that it's because the schools don't allow the smarter kids to get ahead. I think she was mostly referring to being able to read and do very basic math. In other words, it was another preemptive parental strike. My wife and I got the distinct impression that the school doesn't like smart kids. (Maybe they don't like the parents of smart kids who might expect more.)

She also said that their goal up to fourth grade is to pour lots of things into the kids, but don't expect much in return. I wanted to ask her what happens when they finally check in fourth grade and find that there is little there to come out. Remediation.

On one hand, they know that there are smart kids, but they like to pretend that the differences are not that great. This would be fine if they set realistic grade-by-grade expectations. They don't. They can't. When they insist on full-inclusion tracking by age, they just can't do this. They have to water down the definition of education. They don't want education to be a filter by IQ. They try to pretend (to themselves and to parents) that things like differentiated instruction solve the problem, but they know it doesn't. So they go on pretending, going from one "new thing" to another. Sometimes it seems that they really believe what they are saying.

It's not a matter of convincing schools and teachers that some kids are smarter than others. They know that. They also know that most kids would do better academically if they were grouped homogeneously by ability. They just won't do this. Mixed-ability, child-centered tracking by age is more important to them than academics. This is only OK if you water down the definition of academics.

The best will still do OK and the lowest ability kids will get more support, but the vast middle ground will be left to fend for themselves. After a few years, it will all look like external forces. Our K-8 schools keep on with this fantasy and dump the kids (and their problems) across the curriculum and tracking wall into high school. The K-8 schools say that our kids "hold their own", and the kids think they are just not good in math.

I'm of the opinion that a novice is a noveice is a novice. Some novices are smart and some are dull, but they are all capable of learning effectively from explicit instruction and will learn less quickly and/or less thoroughly from less explicit forms of instruction. Though certainly the smarter kids can tolerate the more implicit forms of instruction. Once students gain sufficient domain knowledge, the efficacy of pedagogy may switch to less explicit forms. But I think this switch takes place closer to expert status than most people think.

"But I think this switch takes place closer to expert status than most people think."

I agree. Even through college, you are always learning about new things. Perturbation Theory. Orbital Mechanics. For all of your schooling, you are a novice. I think students always want to be taught directly, in the most efficient manner. Teachers might lead kids down the primrose path of discovery, but I always thought that was annoying. Get to the point! Direct instruction does not prevent student discovery and application of knowledge and skills. I call that homework and projects.

steveh,

This is exactly what Marshall Arlin said would happen.

Enrichment is what schools do to avoid acceleration of high ability children.

I have always been of the type that wants to be told exactly what I need to know, then let me have the freedom to apply it without input.

I have taken so many course's where a problem is presented that requires knowlege not yet learned. As if the instructors delighted in our ignorance. Then the instructor can come in and save us with his expert knowlege, but only after the class has floundered around wasting time.

At the K-16 level, education is like a shark -- it always moves forward. New skills are almost always being learned, so students are almost always learning like novices with respect to these new skills. The discovery and undersstanding is being built behind the scenes as the student uses previously learned (but imperfectly understood) skills to solve newly learned problems. This is why there is really no need for less explicit forms of instruction at the K-16 level, at least if the object is to teach the student more in less time.

Actually, Ken, as I understand it (and I think I do though I wouldn't bet the ranch) I don't think it's the case that kids in K-12 are always in the novice stage.

From what I understand, the boundary between novice and not-a-novice has to do with the acquisition of a "schema," not from the acquisition of x-number of facts.

That is the point at which your speed of acquisition of new facts, concepts, procedures, etc. suddenly jumps.

I think we saw this with Christopher at the end of last school year (6th grade).

Suddenly he could learn new math material quickly. It was a fairly large and obvious change.

His math knowledge is a mess; we're probably going to throw in the towel on Phase 4 (I'll fill everyone in later; yet another meeting with the principal coming up).

However, even though his knowledge is a mess, he acquires new knowledge (or re-acquires old knowledge, which is a CONSTANT issue in this class) much, much more quickly than he did just one year ago.

A schema is essentially an organizing structure, like a map or a closet filled with labeled shelves.

When you encounter a new piece of material you know instantly where it goes, and that's what makes you faster.

(I have NO idea whether a cognitive scientist would sign off on this analogy, but the "schema" part is correct.)

Given what I (think I) understand of the cognitive science of learning, my goal with all students, but especially with slow learners, would be to get a schema inside their heads as quickly as possible.

If we had REAL education research we'd know something about how quickly a student can reach this point, and how many discrete facts/skills/concepts/procedures a student has to learn before he can get there.

I had a "schema-makes-you-faster" experience with autism.

Autism was utterly, utterly bewildering to me for years.

I just didn't get it.

I especially didn't get the infinite array of treatments and cures and educational approaches.

Finally I read Shirley Cohen's TARGETING AUTISM, which she had originally intended to title "A Map of Autism" (something like that - the word 'map' was to have been part of the title).

Shirley organized ALL autism treatments (all of the psychosocial treatments) into two categories:

--developmental

--behavioral

The book was a gift.

All of a sudden I "got it"; I could identify and organize the dozens of ideas and pieces of advice coming my way.

At the time I thought of this gift as a map, which it was.

Today I realize that cognitive scientists would call it a schema.

I'm of the opinion that a novice is a noveice is a novice.

As a nonfiction writer I spend a huge amount of time being a novice. In the past weeks I've been desperately trying to write an introduction to a book on OCD & addiction (and everything in between) for Eric Hollander.

It is HELL.

Although of course I know a little something about OCD (possibly more than a little something) and something about addiction (not so much there) and a lot about autism (which Eric locates midway between OCD & impulse control disorders), I am a novice.

It is SO hard.

But it's been interesting, because I'm living the research & concepts of cognitive science, mastery learning, direct instruction, etc.

I'm going to try to write a post about it.

Let me tell you: try writing a book when you have to look everything up.

Very, very difficult.

I'm just now starting to get a little traction because I'm starting to have a schema in my mind; I'm starting to have a place to put the five gazillion factoids and studies and clinical experiences on these subjects.

So, yes.

My own experience tells me that a novice is a novice is a novice.

I think Gottfredson's curve is correct in that I can go out and find material and teach myself.

But I would be in far better shape if I had a programmed instruction course I could take in the topics I'm now trying to write about.

Rory

Thanks for the link!

Enrichment is used explicitly in our district to avoid acceleration.

Though certainly the smarter kids can tolerate the more implicit forms of instruction.

I've come to question this!

Yes, the smarter kids can "tolerate" more implicit instruction; I certainly wouldn't argue that.

But I read an article by Lisa Van Damme arguing that "pattern recognition" isn't "comprehension."

I have no idea how to evaluate that argument, but it did strike me as true of me.

I think I learned quite a lot of material in K-12 through pattern recognition.

For instance, I can write grammatically, though I don't think I was taught much grammar.

However, I don't understand grammar.

I have almost no idea what any of it means, and I can't use grammar to decipher archaic or complex text. (David Mulroy's WAR AGAINST GRAMMAR made me aware of this point.)

I also learned more than a little elementary math via pattern recognition. I can't think of examples at the moment; I just know that as I've been relearning math I've occasionally come across procedures that I had figured out on my own because they followed from something I had been taught. They were a logical part of a pattern.

But in fact I had no idea why the procedures I had "picked up on" worked, or how to generalize them to other problems or to related procedures.

This has made me wonder whether we ought to be looking at "pattern recognition" per se - do we have a lot of "school smart" kids learning via pattern recognition?

Carolyn said, back when we first met, that I was the kind of kid who learned whatever they threw at me.

That was a terrific observation, and it has stayed with me.

But what does it mean?

How was I learning everything they threw at me? (Obviously I had an extremely fast and good memory, for one thing.)

And what was I learning?

This is an interesting list:

* slow, simple, supervised

* very explicit, hands-on

* mastery learning, hands-on

I noticed the placement of this. So under this list, low-IQ kids get taught slowly, simply, and highly supervised, but only kids with an IQ of 90-100 get taught to mastery?

Try defending that one to a parent of a low-IQ kid.

* written materials, plus experience

As opposed to the hands-on learning we had earlier for the lower IQs. Okay, guys, who wants a doctor who has no hands-on learning?

How about a surgeon with no hands-on learning?

* college format

I don't know about this bloke's college, but the university I went to had heaps of written material and hands-on learning. It wasn't all lectures and one-on-one conversations with the professor.

And a lot of it was explicit too.

* Gathers, infers own information

Yeah, that's a really sensible way to learn about radioactivity. Or medicine.

"Hmmm, I wonder what this glowing stuff is? Do you think it might be dangerous?"

"Okay, let's open the patient up. I wonder what this squiggly bit is?"

hi, Tracy

I've been a little nonplussed by the list myself each time I've seen it.

Does it makes sense as a "limit" - i.e. people with highest IQs learn in all these modes, but people in lowest learn only via "slow, simple, supervised" etc.?

I have to say, though, that I'm not sure this interpretation works altogether (thinking about Jimmy & Andrew).

I think the bottom 3 are confusing.

How different are they really?

I can see where "written materials, plus experience" can be differentiated from "college format"; that distinction was actually pretty illuminating when I read it.

Does it makes sense as a "limit" - i.e. people with highest IQs learn in all these modes, but people in lowest learn only via "slow, simple, supervised" etc.?

It doesn't - why should people in the lowest group not be taught to mastery as much as anyone else? And why would someone think them incapable of learning to mastery?

And I understand that many low-IQ people learn to talk like other children, without slow, simple, supervised education being required. So I wonder if low-IQ kids are limited to learning in a slow, simple, supervised education (they may be, I don't know enough about teaching this IQ group).

On the assumption that "teaching to mastery" has some meaning other than teaching to mastery, then the idea of this info as a set of limits does make a bit more sense.

Incidentally, I just noticed that "Police offer" was rated as a job for someone of average IQ - while "Gathers, infers own information" was rated as something for people starting at an IQ of about 130. How does a police officer get by without gathering their own information and inferring from it?

How do you find college format different from the earlier modes of learning in the list? (Note, I've never attended a US college so there may be differences between them and NZ universities I don't know about).

It doesn't - why should people in the lowest group not be taught to mastery as much as anyone else? And why would someone think them incapable of learning to mastery?

well....I have to say you've spelled out all the confusions I had looking at this chart.

It just doesn't make sense at all.

I definitely know that people in the lowest group learn things to mastery. The things they learn to mastery are simple, but they learn to mastery.

I have to say, this chart gives me some doubts about Gottfredson's work.

Post a Comment